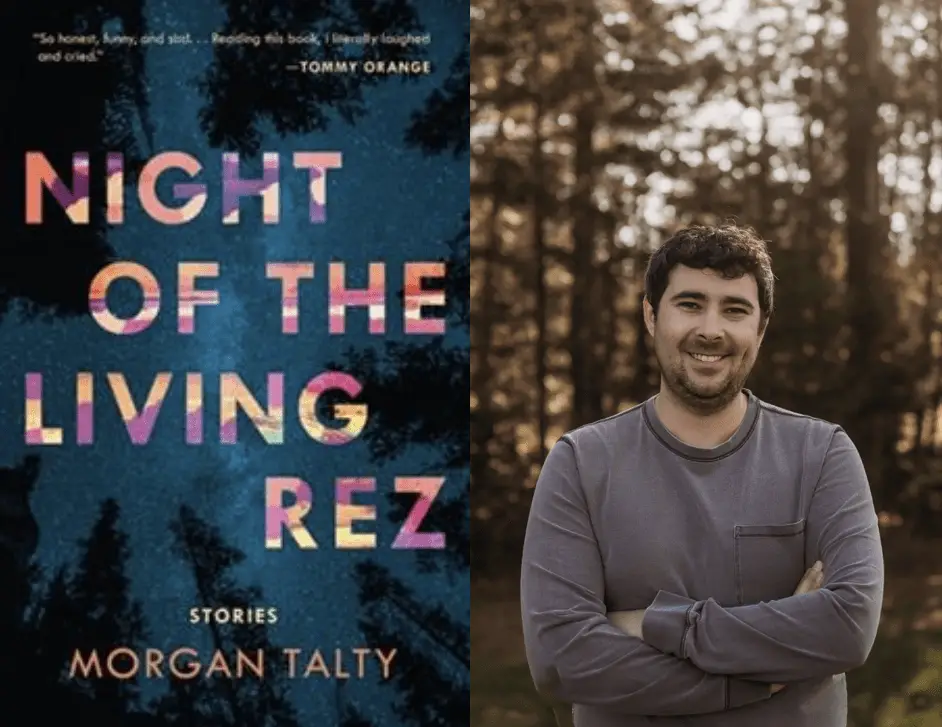

by Montéz Louria

Night of The Living Rez, by Morgan Talty

Tin House Books (July 2022)

Paperback: 296 pages

ISBN-10 : 195353418X

Night of The Living Rez, by Morgan Talty, is a riveting collection of stories that incorporates themes of community while following one Penobscot family and their acquaintances. Throughout each story, Talty writes harrowing incidents and follows the characters through a nonsequential timeline. This nonlinear order highlights the frightening and comedic themes to counter the vexing nature of the characters’ lives. Calling attention to pain and trauma, Talty writes some stories like chilling or suspenseful tales of horror, and in doing so alludes to the zombie film, using a direct reference to George Romero’s 1968 film, Night of the Living Dead.

Published in 2022 by Tin House Books, Night of the Living Rez, Talty’s fiction debut, has become a national bestseller, and received numerous awards, including the New England Book Award for Fiction, the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Fiction Finalist Best Book of 2022, and named a New York Times, TIME, NPR, Esquire, Oprah Daily, Great Group Reads, as well as a Best Book of 2022 by the Tribal College Journal, San Diego Union-Tribune, Ms. Magazine, Writer’s Bone, and Publishers Weekly. The New York Times has called the collection, “Remarkable. . .An electric, captivating voice. . .Talty has assured himself a spot in the canon of great Native American literature.” Morgan Talty is a Penobscot writer and an assistant professor of English in Creative Writing and Native American and Contemporary Literature at the University of Maine in Orono.

This collection’s stories make readers ponder who determines horror and

what horror is for the Penobscot people.

Much like the film, Night of the Living Rez is a metaphor for prevalent social and political issues, including that of finding humor in horror. BIPOC authors must use stories of trauma and pain and make them either funny or anecdotal to keep surviving, and Talty creates stories that specialize in revising and using our own stories to add to a larger narrative. He emphasizes medication, healing, or misuse throughout these stories—important not only to an individual’s well-being but to the well-being and preservation of a community. How can we progress if we are hurting, and the world hurts us? How can we progress when our only narrative is pain? This collection’s stories make readers ponder who determines horror and what horror is for the Penobscot people.

Human conflict against a backdrop of zombie invasion

George Romero’s Night of The Living Dead debuted in a country in racial turmoil. At the time, the audience detested the film because of its allegories to the civil rights movement and racial duress, but it has since become embedded in pop culture and praised for its horror inventions. Night of The Living Dead has become a classic of the zombie film genre, so much so it is considered the zombie movie—the prototype for the zombie trope as slow-moving, bloodthirsty, and of course, the reanimation of a human. Most significantly, this iteration of the zombie, unlike its origins, is not a corpse controlled by magic, and race is insignificant. However, these zombies are a byproduct of human interests. Romero’s characters deal with the internal human conflict against the backdrop of the zombie invasion.

Night of the Living Rez models the same concept. Drug use, sexual assault, familial distance, and poverty are severe detriments to life on the reservation. Talty’s zombies are created by drug use, while Romero’s are the result of radiation from a satellite returning from Venus. Comparably, both zombies are created by human selfishness, and drugs are a metaphor for radiation. The issue is not those who become addicted, but rather, the causes of addiction.

The outsider as zombie

Drug users are often compared to zombies. The Romero zombie has striking similarities to Talty’s characters and is shambling and unintelligible. At the same time, those suffering from the illness of addiction, or the “corrective” measure of methadone, typically have little to no reaction time, decreased reactions, and are unaware of their surroundings, or fatigued. In Night of the Living Rez, readers can find these attributes in characters like Fellis, Frick, and Paige. In the collection’s opening story, “Burn,” Dee is trying to purchase weed without having money to secure the weed. Dee has convinced his dealer he dropped his money and will retrace his steps to look for what he lost. Along the way, readers walk with Dee in the eerily quiet, wooded snowy area. Hearing a strange moan, like a creature, Talty writes, “There it was: a low and breathy noise, and with my cold ear I followed it.” Another guttural sound prompts Dee to call out, investigating and eventually realizing it is his friend, Fellis.

Fellis is shivering, groaning, and his lips are turning purple while frozen in the snow. He is agonizing for help after falling into a drunken stupor. Talty writes, “Instead of the tight braid that shines, Fellis’ hair had come undone, and it was frozen into the snow.”

In this exchange, Talty sets up two essential things: the zombie-like state of Fellis, and the significance of the interaction between dealer and user. Because the collection’s title is a direct reference to Romero’s classic work, much like the beginning of the film, the action is slow and calm before the “crisis” occurs.

At the film’s beginning, readers are introduced to two characters who are already well acquainted and find themselves in a minor conflict that eventually grows and reflects a more significant aspect of the world around them. As in the beginning of Romero’s film, Fellis serves as the character who is zombified against his will. He is similar to a zombie in the sounds he makes, the slow movements, and the obliviousness to his surroundings. Fellis is a victim of addiction, so much so that he must leave the “rez” to go to a methadone clinic, which results in the loss of self and humanity. The zombie is no longer human. It no longer functions as a part of the greater society from which it came. Instead, it is a social pariah causing hysterical panic and fear. Because the zombie is unnatural to the world, its human counterparts shun it.

We see the shaming of the monster in Dee and Fellis’ situation after seeking treatment at the methadone clinic. Fellis and Dee start out using recreational marijuana and social drinking, which could be seen as coping mechanisms to ease the pain and side effects of methadone use. Talty highlights the exclusion Dee and Fellis face within their community:

But we had sacred grounds where seats and peyote ceremonies happened once a month, except since I had chosen to take methadone, I was ineligible to participate in the Native spiritual practice, according to the doc on the rez. Natives damning Natives.

Talty presents a critical issue relating to the scrutiny those who are othered face within their communities and outside societies: the characters are Penobscot living on an under-resourced reservation. Indigenous reservations in the United States are usually under-resourced and purposely forgotten by the United States government. Dee lists the things the reservation does not have, including the treatment facility. Dee and Fellis are already othered by the world, and when they go home, they are outcasts because of their drug use.

The detriments that cause the zombie state are a mystery, another anxiety to be “treated.” Fellis is a product of the environment, the same environment that created zombies, that rejected a zombie film and its allegory to the civil rights movement. That same society can organize the erasure and genocide of Indigenous people without acknowledging the effects of these atrocities. Much like the ignorance of the root cause in zombie films, Dee and Fellis are segments of a greater narrative about colonial ignorance and Indigenous erasure. Dee and Fellis are noticeably absent from spiritual practices. They are now targets to be seen as outsiders. They are the zombies, and the cause of the outbreak is colonization.

In Night of the Living Rez and its film counterpart, Night of The Living Dead, readers are challenged to ponder the concept of the “monster,” which is the “zombie,” which is the “addict” who could be argued to be victims of circumstance.

Using horror and zombie film tropes on the page

The title story, “Night of The Living Rez,” focuses on a sinister, hidden relationship between a delusional, escalated Frick and a traumatized Paige. Talty directly plays with zombie references in this story. Paige, David’s sister, takes an unusual interest in zombie films. Towards the end of the story, another Romero film, Land of the Dead, plays on the television while their mom is out shopping.

The film’s reference foreshadows the moment when David discovers Frick attempting to assault Paige. David hears slow, guttural grunts from the zombies on the television as he walks into an eerily still house. The television’s volume is abnormally high compared to the stillness of the usually lively house. The contrast between the sounds coming from the television and David’s cautious entrance into the house heightens the intensity. Talty uses horror and zombie film tropes to parallel the characters’ horror—the detriments of substance abuse and the ongoing effects of unprocessed trauma.

In another incident of foreshadowing, David is curious about a woman on the bus with a super soaker in her jacket. He associates the woman with another woman he’d heard about, who sprayed customers with her urine in a grocery store. David assumes the women are one and the same, mainly because of the Gatorade bottle and the super-soaker tucked in her jacket. These details add tension and suspense. While reading, one may wonder why David is fixated on this woman, but much like horror films, there are obscure details that aid in setting the tone. There are parallels between this mystery woman and Paige—both first appear aloof and unexpectedly enact harm upon others. This predicts Paige’s distress later in the story, when Frick becomes the catalyst for Paige’s rage and tragic downfall.

The is a horror story, and unfortunately, Paige is the “final girl,” in the traditional sense, and (made out to be) a “monster.” She endures trauma. She is fighting a “masked” villain, and the people around her are also affected by her trauma, even though it was hidden from David and their mom. Paige morphs into a character that neither her brother David nor readers recognize—so much so that she is mistaken for a pugwagee—creatures who were once children but cursed because of their thievery. At the same time, Frick takes on the traditional horror villain role, and we follow his transition.

When David comes home from a trip with his dad, he and his mom exchange questions about the whereabouts of Paige and Frick. Mom has not seen Frick but worries about Paige’s strange behavior. Mom tells David, “He’s been weird for weeks now. Last Friday—in the middle of the night—I found him shivering in the kitchen with a tablecloth over his shoulder. He was sleepwalking and kept saying the Jesuits were coming.” At this moment, Frick is different from what we have seen before; his behavior is more bizarre. We then learn that Frick has been over-using Ambien to aid with insomnia. The combination of alcohol and Ambien makes him detached from reality and incoherent. Mom tells David, “I don’t know—I think something’s wrong with him. He’s been taking Ambien for sleep, which would explain his sleepwalking.’ She went into the living room and checked how much wine Frick had drunk.” Frick is still present but not as cognizant. He is becoming another zombie.

Instead of the slow-moving, bumbling zombies of Night of the Living Dead, similar to Fellis, Frick evolves like the zombies in Romero’s film, a work directly referenced by Talty in the story. Frick is aware enough to be violent yet detached, cognizant enough that when David finds him assaulting Paige, he recognizes him—calling his name as he continues the assault. Talty writes, “He yelled my name and Frick hit her and then looked at me over his shoulder and called me a fucking Jesuit,” and “…I backed down the hallway and watched him, and he mumbled this was his wigwam, that white people weren’t welcome…”

Frick is a zombie, so much so that, like a “zombie virus,” he infects Paige because of his rage and drug abuse, though here, Paige’s transition is caused by trauma and violence. It comes unexpectedly for Paige. Later, she is mistaken for a creature in the woods as she stumbles and grunts toward David and his friends, incoherent and unaware when David discovers her wandering. After bumming a cigarette, she yells obscenities and calls Frick a pig. Although she never manifests the extreme behaviors of Fellis and Frick, Paige has been changed by Frick’s assault. Zombies are the byproducts of humans, their curiosity or selfishness. Frick demonstrates curiosity, selfishness, and being a victim of colonization- drug use and, ultimately, violence—in fact, violence in most BIPOC communities is most often linked to the remnants of colonization.

Morgan Talty’s riveting set of stories explores the consequences of tragedy. Throughout the collection, in stories that mirror the horror film, he challenges readers to think about the true terror of survival. The title itself, its play on Romero’s classic film, examines the nature of the human condition as well the demise of humanity. Talty uses the same ideas to convey the nature of living. Essentially, living, or existing, can be as frightful as a horror film.

As an Amazon affiliate, LitStack may earn a commission at no cost to you when you purchase products through our affiliate links.

Comments are closed.