Ideally, writing a mystery requires careful planning, a mound of research, and the ability to think more deviously than the reader.

Notice I said “ideally,” because I’ve written mysteries where *I* didn’t know the solution to the crime until after I wrote the last chapter. So it is possible but not recommended. It’s a path that is frustrating, complicated, and will have the author almost literally pulling out their hair. For those who don’t want to follow my dubious example, I’ve going to break it down into small steps.

Step One: The Setting

This is sort of like the chicken and the egg: which comes first depends on how your brain thinks. I choose setting for the purposes of this article because setting is character, and setting is an element that is incredibly important to readers. Much of what is specific to any crime depends on setting.

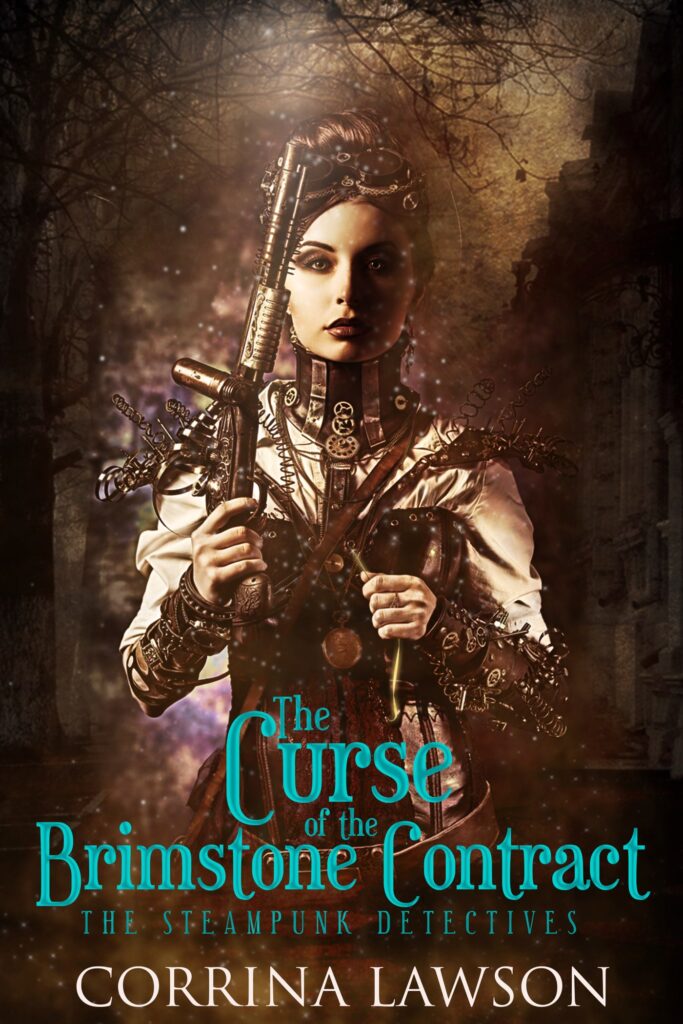

When I wrote The Curse of the Brimstone Contract, I talked about how I couldn’t write the characters until I settled on the worldbuilding. The murder that occurs in the first chapter depended on the worldbuilding, as it informed the magic that caused the murder. The clues, too, are dependent on that world.

A modern example would be the movie Knives Out. Its’ setting is mainly the house where everyone has gathered after the death of patriarch Christopher Plummer. The trick to how the murderer committed the crime is dependent on the house’s layout as well. The setting is as much a character as everyone else in the story.

When one thinks of Sherlock Holmes, the first image that comes to mind is him stalking the streets of Victorian London. (Even the modern adaptations can’t resist playing with that setting.)

Nick and Nora Charles belong in the roaring 1920s world of excess. Kinsey Milhone belongs in her office in Santa Teresa, California. Spenser belongs in Robert B. Parker’s rough-hewn Boston. Easy Rawlins belongs in post-World War II Los Angeles.

Step 2: The Detective

Yes, this is entwined with setting. They are hard to separate and there is a great deal of crossover but it’s not complete. Different characters will interact with the setting in different ways. In Knives Out, the ultimate insider, Marta Cabrera, is faced off against the ultimate outsider, Benoit Blanc. Their intellectual duel and ultimate team-up depends on that dynamic.

What’s your detective’s main skill? Background? Worldview? All of the answers to these questions will inform the detective’s approach to the crime. In Above the Fold, coming out next year, my two detectives, Trisha and Grayson, have completely different methods. She’s a relentless force, ready to confront anyone, dig anywhere, and believes the best way to the truth is to be the ‘boots on ground,’ so to speak. Whereas Grayson is careful, gathers information, and avoids confrontation until he believes he knows the answers already. Hopefully, that makes for a fun contrast for the reader.

Michael Connelly said in an essay written about his best-known creation, Hieronymus Bosch, that much of the character depends on a motto Connelly developed: everybody matters or nobody does. For Trisha, it would be “the truth matters,” and for Grayson, it would be “dig under the surface.” Yes, that’s shorthand for more complicated characterization but it’s shorthand that helps when plotting out a mystery.

Who the detective is will determine how they go after clues and how they react to those clues.

Step 3: The Clues

In a perfect world, your fictional crime would be plotted out like the beginning of a Colombo episode, where the murder is meticulously planned. Some clues happen at this stage but the viewer doesn’t yet know how Colombo will use them to solve the crime.

As an author, you’re the murderer, and you’re planting clues at the crime that will help your detective solve the murder. That’s why it’s good to know, AT THE BEGINNING, the exact details, the clues that matter, and the clues that are red herrings.

If you’re wondering if I live in this perfect world of plotting, the answer is “I wish.”

Often, I have the crime happen, place some clues, and then realize the clues are lame, that they’re not enough, or they’re too obvious, or just too ridiculous. That sometimes means later changing the method of the crime to backfill in better clues, writing more red herrings into the story, and tossing out entire scenes of deduction to replace them with different ones. This is not a method I recommend as it requires a spreadsheet much like that meme from Community.

But, ultimately, it works after trial and error. I often wonder how Colombo writers did it working on short deadlines or how any weekly television show manages to create any mystery week-to-week, much less a compelling one.

But the answer is that they’re probably relying heavily on setting and cast familiarity to keep readers interested rather than writing a spectacularly plotted mystery. That’s probably why savvy viewers know the killer is often the most famous guest-star or that person that they first interviewed that seemed innocuous. However, mystery writers have one, maybe two, books per year. They have to deliver to the reader and not rely on coasting.

Step 4: Emotional Involvement

The reason why stories involving cold cases pull at us is because as the story opens, we see the emotional damage wrought on the survivors of the crime. We want to give answers to them because their grief and loss is so apparent. That is one good way to hook a reader or viewer.

The other way, of course, is to have the readers invested in your detective and your setting. The pioneer, Arthur Conan Doyle, did this by writing in an audience surrogate, an everyman, John H. Watson, to narrate the Sherlock Holmes stories. They’d be a much different emotional experience if Holmes was the one telling the tales.

Often detectives are investing crimes that hit close to the bone, that either have emotional resonance to their past, are directly connected to their past, or their present depends on solving the crime. The story that comes to my mind first for Sue Grafton’s Kinsey Milhone: the one where she’s investigating a case involving her ex-husband.

Or, alternatively, the detective isn’t emotionally invested at all but the suspects and the survivors of the crime are compelling. See: Knives Out. No one has any clue what makes Blanc tick. That’s fine because we find out what makes every single suspect tick, especially through the eyes of Marta.

Emotionally invested doesn’t have to mean tragic emotions either. One of the best episodes of Castle, “Wrapped Up in Death,” concerned a murder at a museum, a potential curse, and several references to Scooby-Doo.

And, yes, the original Scooby-Do: Where Are You? cartoons are great mysteries. They create memorable detectives to spend time with, they always feature a range of suspects, the gang is always looking for clues, and each episode has a unique sense of place. One could do worse than Scooby-Doo: Where Are You as a guide to writing mysteries. And, as the linked article talks about, they also had a worldview: the real monsters are people.

Step 5: The Big Reveal

I consider the Big Reveal essential in a great mystery. The Big Reveal lets the reader in on the fun. The big reveal allows that moment of catharsis.

It doesn’t matter if it’s in a mansion where the suspects have gathered, or if it’s Colombo turning around with his last, final “just one more thing,” or if it’s Holmes explaining how he deduced all that, or the final battle between detective and killer. The Big Reveal is to show readers how they got here.

Sometimes it’s followed by the Big Physical Face-Off but not always. Sometimes it’s “if you weren’t for you meddling kids!” Sometimes, it’s Holmes and Watson running through Dartmoor in pursuit of the killer. Sometimes, especially in a noir mystery, it’s a gut punch that makes the detective question their entire life. The reveal in Alex Segura’s Secret Identity is like that.

It’s the rare mystery that solves it all but ends without a catharsis, with the detective walking away from this confrontation. Some consider Chinatown a classic because of its’ ending. I consider it a cop-out.

The Steps to Writing a Mystery: Do It Your Own Way

In the end, each author writing a mystery will do it differently. They’ll mix and match the steps I’ve outlined and work on them in an unique order. Sometimes this method will change from story to story.

Some will do the meticulous plotting and spreadsheets before beginning, allowing them to write a first draft that needs little revision. (If that is you out there, I’m only a little bit jealous. Okay, a lot jealous.)

What’s important is that the story contains all these elements and ends in a satisfying way. The ending of a book will sell the next book.

If you get really lucky as a writer, there will also be enough in the story that allows the reader to enjoy re-reading the mystery, even though they already know the solution. That’s a wonderful bonus.