Enjoy this classic LitStack Review by Lauren Alwan of William Styron’s Sophie’s Choice.

In This LitStack Review of Sophie’s Choice

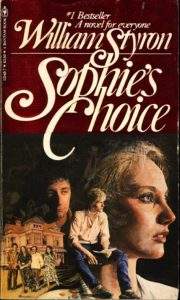

I first read Sophie’s Choice in a Bantam paperback 1979 edition.

Sophies’s Choice is not a true story, per se. Styron based his novel on his memory of a real-life woman named Sophie, a survivor of Auschwitz he met during his youth in Brooklyn. From that encounter, he constructed a character, not Jewish, but Polish Catholic. The cover montage featured a glamorous and pensive Sophie Zawistowska, before Meryl Streep’s role in Alan Pakula’s 1982 film became forever imprinted on the character. In those days, I did most of my reading in bed—a mattress on the floor by the light of a drafting lamp clamped to the windowsill. I lived in San Francisco then, working part-time while I finished art school, and it’s embarrassing now to admit how little weighed on my mind in the days of reading the novel.

Back then, I sought the familiar in fiction, and knew nothing about Styron or his book, which I think my sister passed along saying it was “a good read.” Sophie’s Choice, Styron’s sixth novel, is number 96 on the Modern Library’s list of 100 Best Novels. In 1980, the book won the US National Book Award for Fiction, and the year it was published, the South African government banned the book for being sexually explicit. It was banned in then-Communist Poland for “its unflinching portrait of Polish anti-Semitism.” American school libraries also banned the book, its sexual content deemed unsuitable for minors—though recently that under challenge in one school district.

“Guilt Is Everywhere.”

In 1979, I knew as much about the Holocaust as any other 20th-century-born, third-generation, college-educated, half-Jewish Unitarian. Which is to say, not much. Both my mother’s parents had relatives in Europe during the war, some of whom fled the States, but rarely were those tales of escape spoken about to their grandchildren. Still, as John Gardner wrote in his 1979 New York Times review, “guilt is everywhere,” a statement that is as true for our family as any in which there is unspoken grief, loss, and shame. Sophie’s Choice puts these front and center, but I was a naïve reader, raised with what amounts to a protective shield of silence, and I read those aspects of the novel at a remove, and instead, was drawn in by the intricate plot, the love story (or stories, to be more accurate), and the voice of the narrator, Stingo.

Gardner called the book a “splendidly written, thrilling, philosophical novel on the most important subject of the 20th century.” That assertion must have seemed radical, for surely there were other events foremost in the collective memory—the presidency post-Watergate? The Iran Hostage crisis? Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan? The assassinations of John Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King?

Here’s Gardner again:

[Styron] shows us how serious this novel is as not merely a story of other people’s troubles, but a piece of anguished Protestant soul-searching, an attempt to seize all the evil in the world—in his own heart first—crush it, and create a planet for God and man.

There’s a story that when Styron was writing The Confessions of Nat Turner, his friend James Baldwin glimpsed the early drafts and said, “Bill’s going to catch it from both sides.”

That was a trend that would continue for Styron, as Sophie’s Choice brought controversy yet again. The thesis of the novel, that the evil of Nazi Germany threatened not only Jews but humanity as a whole, received sharp criticism and was declared revisionist history. On the other hand, Sophie’s Choice challenged prevailing opinion, which amounted largely to silence and an uncritical response to the Nazi atrocities. Thirty years in the past, the Holocaust was still on the periphery of American Jewish consciousness, but with the novel’s publication, Styron had a role in challenging prevailing thought, so much so that Sophie’s Choice came to be considered a revisionist view. Then, in 1978, NBC aired a four-part miniseries on the Holocaust (which garnered both praise and controversy as a subject). That same year, Jimmy Carter established the Commission on the Holocaust, which would lead to the Holocaust Memorial Museum. Two years later, Vanessa Redgrave portrayed Fania Fénelon in the film Playing for Time, based on the memoirs of the French pianist and cabaret singer who survived Auschwitz by forming an orchestra to play for the SS. By the mid-1980s, Holocaust discourse would emerge as a distinct idea, differentiated as Peter Novick says, “from other Nazi atrocities and from previous Jewish persecutions, singular in its scope, its symbolism, and its world-historical significance.”

Sophie does not narrate the story.

The narrator is twenty-two-year-old Stingo, a young writer who’s recently arrived in New York City from Virginia. Young and ambitious, he loathes his job as a manuscript reader at McGraw-Hill. The discontent manifests as a “work stoppage” that culminates in his letting loose a half-dozen balloons from his 20th-floor window at McGraw-Hill, a prank for which they fire him. Unsure of how long his funds will last, Stingo realizes he must finally write his novel, a point at which fate intervenes as a letter from his father. Stingo turns out to be the recipient of a dubious family inheritance, one based on the sale fifty years before of Artiste, a family slave:

Years later I thought that if I had tithed a good part of my proceeds of Artiste’s sale to the N.A.A.C.P. instead of keeping it, I might have shriven myself of my own guilt, besides being able to offer evidence that even as a young man I had enough concern for the plight of the Negro as to make a sacrifice. But in the end, I’m rather glad I kept it.

Stingo goes to Brooklyn, rents a room in a Flatbush house to write his novel, and there encounters his neighbors Sophie and Nathan.

Styron’s sentences are rich, fluid, though sometimes have a too-conclusive, overwritten quality. As a result, Sophie’s nightmarish account, recounted by Stingo in retrospective installments that alternate with present-time action, is both heightened and dampened by the florid style. Here, Stingo recounts her arrest in Krakow (for smuggling a contraband ham), a crime for which they send her and her children to Auschwitz:

They found the four-kilo cut of ham almost immediately. Her stratagem—fastening the newspaper-wrapped package to her body beneath her dress in a way that would make her appear corpulently pregnant—was shopworn enough by now almost to call attention to itself rather than work as a ruse; she had tried it anyway, urged on by the farm woman who had sold her the precious meat.

“They’ll surely catch you if they see you carrying it in the open. Also, you look and dress like an intellectual, not one of our country babas. That will help.”

But Sophie had not foreseen either the Iapanka or its thoroughness. And so the Gestapo goon, pressing Sophie up against a damp brick wall, made no effort to conceal his contempt for her doltish Polack dodge, extracting a penknife from the pocket of his jacket and inserting the blade with relaxed, almost informal delicacy into that bulgingly bogus placenta, leering as he did so. Sophie recalled the smell of cheese on the Nazi’s breath and this remark as the knife sank into the haunch of what had been, until recently, contented pig.

“Can’t you say ouch, Liebchen?” She was unable, in her terror, to utter anything more than some desperate commonplace, but for her small pains, received a compliment on the felicity of her German.

The scene, though overwritten, is still terrifying, the language ornate and weirdly sexual, a feature of Stingo’s young point of view. From his first encounter with Sophie, he obsesses about her, his thoughts simultaneously idealizing and degrading her. In the decades since the novel’s publication, this has worked against the novel, because there is an uncomfortable complicity in the portrayal of a concentration camp survivor as a point of sexual desire (spoiler ahead: Sharon Oster, in her essay “The Erotics of Auschwitz,” reminds the reader that at the time Stingo tells the story, Sophie is already dead). Embarrassingly, that point eluded me on my first read, ignorant as I was about feminist thought beyond the news of women’s protests I’d seen in Life magazine a decade before. (This aspect of the novel is well covered by Ed Champion here.)

A Testament…to the Power of Styron’s book

On this second read, however, Sophie’s portrayal, her life before the war, her role in the Polish resistance, her arrest and imprisonment and subsequent life in Brooklyn with the charming and dangerously bipolar Nathan, are all there, but in the end altered by Stingo’s obsessive desire. I think again of Gardner and the “Protestant soul-searching” he declares essential to Styron’s vision and the larger sphere of the story. Within a decade after the novel’s publication, identity politics and literary theory would bring about a consciousness for “other people’s troubles” to be told in the speaker’s own voice. To a contemporary reader accustomed to ownership of those narratives, Sophie’s Choice will likely feel a bit off, as Sophie’s view is appropriated. But these are the terms of the novel, and in the end, still worth reading.

In fact, the novel endures, and the title has become a familiar figure of speech—used to signify the impossible decisions, a Sophie’s choice. On that point, this read proved more difficult for me, since I have a daughter now, and contemplating any sort of forced separation from her was frightening enough to make me dread what I knew was coming. As I moved through the chapters—the scene in question comes near the end of the novel, the first of three high dramatic moments that take place in the last 40 pages—and I felt a sickening fear, a testament itself to the power of Styron’s book.

Yet even on that early read, that scene is surely the one that caused the novel to enter my consciousness, took me out of my easy life, and made me uncomfortable. That is, after all, what novels do: they make the reader see things she didn’t see before.

That summer, we would pack up our few pieces of furniture and give notice on the flat on Clement Street. My sister and a friend rented a flat in North Beach, on Stockton Street, and I was rootless for the summer. In those years my life was insular, the life my grandparents, who’d lived through the war, wanted for me, and for all their grandchildren.

— Lauren Alwan

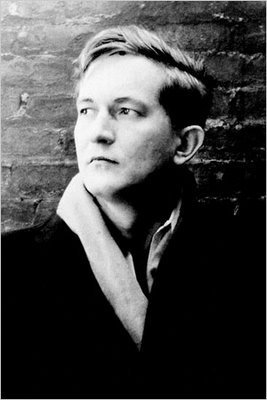

About William Styron

William Styron (1925-2006) , a native of the Virginia Tidewater, was a graduate of Duke University and a veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps. His books include Lie Down in Darkness, The Long March, Set This House on Fire, The Confessions of Nat Turner, Sophie’s Choice, This Quiet Dust, Darkness Visible, and A Tidewater Morning. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, the Howells Medal, the American Book Award, the Legion d’Honneur, and the Witness to Justice Award from the Auschwitz Jewish Center Foundation. With his wife, the poet and activist Rose Styron, he lived for most of his adult life in Roxbury, Connecticut, and in Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts, where he is buried. Source: Amazon.

Other LitStack Resources

Be sure and discover other LitStack articles by Lauren Alwan, including reviews and recommendations.

You can find and buy the books we recommend at the LitStack Bookshop on our list of LitStack Recs.

1 comment

What a wonderfully written piece on Sophie’s Choice. I must reread the book. Thank you for posting this essay.

Comments are closed.