A debut review by writer Emmie Finch of the books of Pellinor, by Alison Croggon.

In This LitStack Review of Pellinor

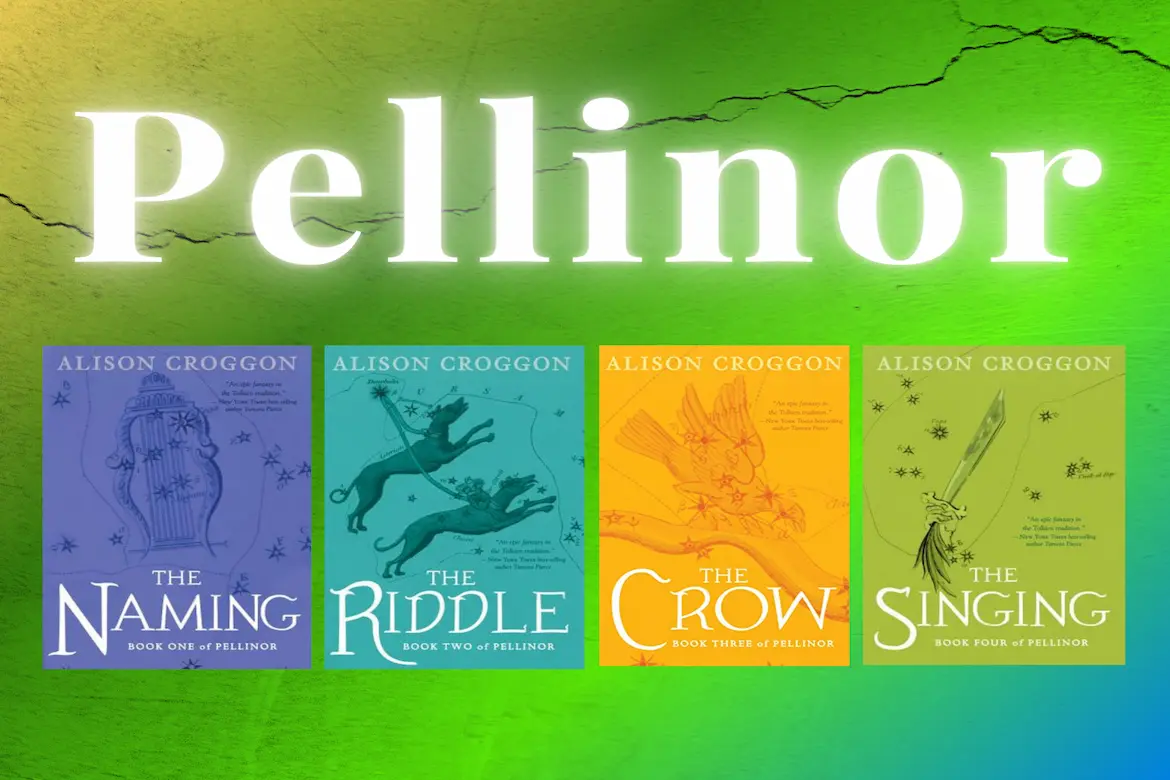

Pellinor – The Naming, The Riddle, The Crow, The Singing

The publishing detail page at the front of each of the four books of Pellinor list the following categories: supernatural‑fiction; magic‑fiction; fantasy. Each of these genre classifications is accurate but there is so much more to this series. In the four books, the author, Alison Croggon, skillfully depicts characters and events with eloquence, loving detail, and tremendous focus and through this produces a story of sublime creativity and adventure.

Pellinor is a world where magic is an accepted norm and magical and non-magical people live in accord through mutually beneficial relations. In this story, a great unbalancing is taking place and we follow a small group of people struggling to overthrow the evil source and restore balance. Each book draws us more deeply into the good and evil aspects of this world and brings us closer to the inevitable confrontation between the two.

The story begins with the meeting of two key characters. The young heroine, Maerad, and the long-lived Bard, Cadvan. Maerad, barely sixteen years old, is an orphan and a servant in a bleak, despairing fortress called Gilman’s Cot. Surly, stubborn, and innocent in turn, when she is not tending to her assigned day-to-day labors, she survives the trials of her existence by using her strangeness to corral predictable male savagery into submission through dormant magical abilities she is unaware she possesses. She also entertains the churlish, musically undiscerning louts of Gilman’s Cot by playing the lyre her mother left her when she died, and that is Maerad’s sole possession.

Maerad is a thoughtful and predictably moody teenage girl whose inner world is shaped by the harsh reality of the bleak world she lives in and her fleeting hopes of escape.

When Cadvan, a traveling Bard, arrives at Gilman’s Cot he immediately recognizes there is something special about Maerad because she can see through the glimmerspell that should render him invisible. Following his instincts and the promptings of his bard senses, he offers to take Maerad with him when he leaves and she agrees. From there, the story plunges into action and adventure that traverses the breathtaking landscapes and multi-faceted scenarios the author vividly and meticulously depicts. The societies we visit, both magical and mundane, atrocious or flawless, come to life in the imagination as we journey through the story.

Geography and Atmosphere as Characters

On page one of the first book (The Naming), a description of Gilman’s Cot introduces us to the series:

Gilman’s cot was a small mountain hamlet beyond the borders of the wide lands of the Inner Kingdom of Annar. It nestled at the nape of a bleak valley on the eastern side of the mountains of Annova, where the range split briefly and ran out, like two claws, from near the northern end. Its virtue, as far as the Thane Gilman was concerned, was its isolation; here he could be tyrant of his domain, with nothing to check him.

The images in this description of the landscape create a strong visual impression of the geography. Yet we also perceive the threatening atmosphere of Gilman’s Cot and glimpse the essence of its tyrannical master: bleak valley . . . split briefly and ran out, like two claws . . . isolation . . . tyrant of his domain . . . nothing to check him . . . This vivid intertwining of sensory intake is woven throughout the story so the images and atmosphere of Pellinor come to life as you read.

. . . In the street below, the cobbles were white with moonlight but pooled with black shadows. It appeared peaceful, but anyone watching for any length of time—a bird, say, on a roof—might have thought, blinking in the deceptive moonlight, that their eyes were playing tricks. For sometimes it seemed that the shadows swelled and distorted, as if something black moved stealthily against the buildings, but then, when you shook your head, there was nothing there. If the watcher had been patient, after a time it would have become clear that two darkly cloaked figures moved stealthily below, keeping always out of the light, slinking from doorway to doorway . . .

Minions of the Dark

As equally compelling as the geography and landscape of Pellinor are the fiendish manifestations, monstrous constructs, corrupted creatures, and various other aspects of the dark that populate the land, whose behavior and appearance thrill and chill. The creatures, constructs, and fiends we meet throughout the story create an atmosphere of menace, madness, and terror that is imparted more through the descriptions of their nature and appearance and by the impact they have upon people and the environment rather than through their actions and deeds, which like most evil sorts involves killing, conquering, terrorizing, and destroying. As you read, you cannot help but wonder, with a frisson of unease, how such monstrosities were created and by whom for it is never clearly stated.

Dogsoldiers were a weird mixture of metal and flesh: it was hard to tell where their armor ended and their bodies began . . . They were heavily built, . . . But it wasn’t their size, or that they so clearly existed only in order to kill and maim, that made him recoil. He had caught a glimpse of the face under a dogsoldier’s iron helmet, a face disfigured by the monstrously fanged steel muzzles that projected from its cheekbones, and he saw its eyes. Human eyes, with a human intelligence. In that moment, he realized with a shock that the dogsoldier was, or had once been, a human being . . .

Denizens of the Light

Just as evocative are those who counterbalance the creatures and fiends of the dark. Otherworldly beings, some whose lives span the ages and for whom the trials of humanity play an infinitesimal part but upon whom they must depend to help right the imbalance that threatens all. Beings not of the dark, perhaps, but equally fierce and uncompromising. Beings who can, as Cadvan expresses, “turn like fire in a trice from benign to deadly.”

. . . in the chair sat a tall woman. She was robed in white, and her hair fell freely down her shoulders almost to her feet, like a river of silver. Her face seemed at once young and infinitely ancient, as if she were the painted image of a queen who had reigned in ages long past which, by some enchantment, lived; and her glance pierced Maerad with a strange thrill, as if she had stepped into a cold river. She bore no circlet or jewel or staff of authority, yet Maerad knew at once she was a queen of great power . . .

The Humanity of Pellinor . . .

The characters and people we meet throughout manifest behavior and characteristics we can easily identify with, in ourselves and in others. They struggle with feelings and grapple with personal choices even in the midst of world-altering turmoil and trauma. They grow and develop and reveal new aspects of themselves—both good and bad—in response to the circumstances, which makes them very real. They make mistakes, they lose their temper, they make poor choices, they argue, they jest, they fear.

Hem was the most silent human being Maerad had ever met. He rode with Cadvan . . . and all day he said nothing . . . Hem was tense, a jangle of nerves, watchful and wary behind his roughly cut hair. At times he seemed much older than his twelve years; his face was at odd moments world-weary, like an old man who’d seen too many horrors, and yet at other times he was disconcertingly a little boy. . . .

Humanity Tempted

Very seldom in conflicts between good and evil are those of the dark tempted by the light, whereas those of the light are frequently tempted by the dark. In this story, some who have a duty to honor the light succumb to their darker nature by embracing the influence of the dark and thereby contribute to the conflict by betraying friends, colleagues, obligations, and themselves.

. . . Directly before her, on the other side of the table, stood a tall, thin Bard dressed in white robes. He was staring straight at her, and his nostrils were pinched white with rage. He had a fierce, hooked nose set between dark, flaming eyes, and deep lines furrowed between his nose and his mouth. His brow was high and white, and also deeply lined. It was a proud, intelligent face, pitiless as a hawk at the moment it stoops for a rabbit; but it was cold, as a beast never is, and beneath the coldness Maerad sensed a bitter cruelty. So Maerad first perceived Enkir, First Bard of Norloch . . .

And Those Somewhere in Between . . .

Then there are the people of Pellinor who live more ordinary lives. Those whose day-to-day existence teeters naturally somewhere between good and evil. People who experience the greater struggle through the ripples it creates, hoping there will be no flood. People whose lives are marked, destroyed, or ended by a conflict they barely comprehend but during which corruption, disease, and harm seep into their lives like a toxic fog, spreading fear, doubt, suspicion, despair, illness, and death.

One morning they walked through a small town . . . The houses were mean and poor, little more than hovels holding each other up, patched with scavenged bits of wood or planks or stone. The street stank of middens, and was pitted with deep ruts filled with icy water. Ragged children peered at them from behind tumbledown fences or mossy water butts, their eyes wide with fear; Hem noticed with a pang that he saw none older than about nine years.

Music and Lore

The music and lore of Pellinor offer a lovely, poetic, and mystical presence throughout the story. Expressed through songs, poems, ancient texts, and riddles:

When Arkan deemed an endless cold

And greenwoods rotted bleak and sere,

The moon wept high above the world

To see its beauty dwindling:

To earth fell down a single tear

And there stepped forth a shining girl

Like moonlight that through alabaster

Wells, its pallor kindling.

A wild amazement fastened on

The Moonchild’s heart, and far she ran,

Through all the vales of Lirion

Her voice like bellnotes echoing:

And from the branches blossoms sprang

In iron groves of leafmeal wan,

And Spring herself woke up and sang,

The gentle Summer beckoning.

Magical Practice

Ordinarily, the practice of magic in the Kingdom of Annar is used to teach, heal, aid, and protect, During conflict its use expands to include defense and most bards are taught the basic skills of war craft.

“The Knowing is divided into the Three Arts, all of which are of course interconnected, in reality, the one stream. They all serve the Balance . . . We call the Three Arts the Reading, the Making, and the Tending. The Reading is the knowledge of the High Arts, the histories, the languages, the song, the lore, the tracing of the high forces that shape and bend this land. It’s what is most commonly thought of as magic, but it is also as simple as reading and writing. The Making is exactly what it says: it means the making of music, painting, building, jewelry, smithing, writing, dancing. The Tending is the knowledge of growing, husbandry, forestry, childcraft, wilding, herbs, healing, bird lore, and so on . . .”

Something Like Perfection

The excerpts I have included are memorable moments that leap out at me while reading. Moments akin to those times in real life where the smaller details of a greater happening impact just as profoundly as the happening itself—like the long, crooked crack traveling up the side of a building wakens memories of the earthquake that caused it. I have read this series of books three times and each time I have been just as thrilled and eager to visit and just as awed by how well the books are written.

I have often attempted to describe the phenomenon that occurs when someone writes something that is so seamlessly crafted it verges on perfection but the description eludes me—as Toni Morrison once said: “If I knew the sentence, I wouldn’t have written the book.” The closest I have been able to manage is: each description, each character, each turn‑of‑phrase tells a complete story.

If I were to liken the Pellinor books to another series of equally superb writing it would be J.R.R. Tolkien’s Hobbit series, with the key distinction being that the Pellinor series lacks Tolkien’s predominantly male perspective—and it is with grateful appreciation that I observe how society has advanced to the point where most films, books, and stories nowadays at least render women as titular equals to men (pun intended).

A Heroine, A Person…

Throughout the Pellinor series (the first book was published in 2002), we experience Maerad developing as a person, as a Bard, as a heroine. She is neither sexually iconic nor is she written as a vain character. We glimpse her appearance through the eyes of others from time to time, but it is the development of her psyche and the expressions of her soul that are shared. This is equally true of Cadvan, Hem, Saliman, Ardina, Zelika, Arkan, and so on. Even the animals have a character and spirit of their own: Imi, Darsor, Irc, etc.

The landscapes and societies Ms. Croggon depicts throughout the books utterly transform. They are as vivid and clear as if the author was detailing what appears in a photograph. Through this amazing clarity the world of Pellinor unfurls like a tapestry: vast stretches of woodland manipulated by otherworldly influences; powerful schools of grace and beauty where magic and music are taught; veiled forests home to ageless, elemental beings; desolate landscapes where civilizations once thrived; mile after frozen mile of unrelenting snow and ice; bleak training camps where brutality and butchery are learned; entire regions corrupted into evil domains; sprawling mountain ranges, benevolent glades, storm ravaged seas, shadowy ruins, underground cities . . .

A Seamless Blend

The final sequence of events always has me shaking my head with wonder because in so many good versus evil stories the reader is inundated with one climactic scene after another until they are desensitized enough to say at the end, “Is that it?” Not so here. Concluding events progress like the inexorable drawing of a bowstring and release with a seamless blend of simplicity, symmetry, and fantasy.

Pellinor immerses the reader, stimulating their imagination and intellect as they journey through this beautiful and beautifully written story. It is a reading adventure I wholeheartedly recommend.

~Emmie Finch

About Alison Craggon

Alison Croggon is an award-winning Australian poet whose work has been published extensively in anthologies and magazines around the world. Her plays and opera libretti have been produced in Australia, and she is also an editor and critic. She began to write the books of Pellinor when her oldest son, Joshua, was reading fantasy. “I had forgotten how much I loved this stuff when I was a kid, and Josh’s reading reminded me,” she says. “My first real ambition as a child was to write a fantasy novel. One day I sat down and started writing a story. I had no idea what would happen, but one character appeared, and then another, and before long I had to finish the story to find out what happened.” That story was THE NAMING. She says she was surprised by how the book seemed to unfold, already formed, before her. “Perhaps it’s been waiting to be written for thirty years.” Alison Croggon lives in Melbourne, Australia, with her playwright husband and their three children.

Other Titles by Alison Croggon

Other LitStack Resources

Be sure and check out other Litstack Reviews and LitStack Recs to find what you should read.