Table of Contents

A Story Deepened by a Poetic Sensibility

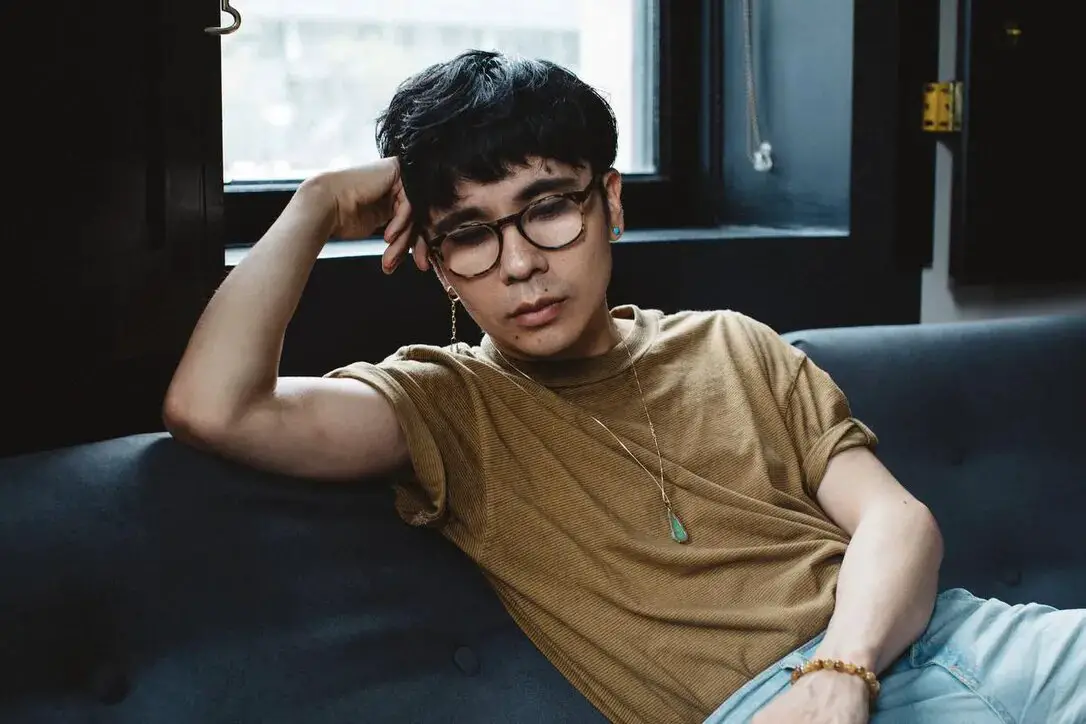

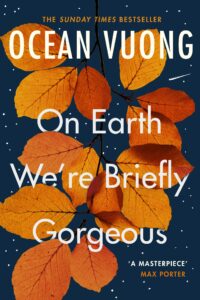

Ocean Vuong’s 2019 novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, is a perfect read for National Poetry Month.

It’s a singular book, bringing together the blended genres of the novel, poetry, and memoir, and is a vivid portrayal of what it means to be an immigrant in America and a survivor of the legacy of war.

The narrative voice in On Earth, like Vuong’s, is keenly observant, and sharp in its critique of what it means to be an outsider: “One does not ‘pass’ in America, it seems, without English.” We follow the story of Little Dog, who arrives in the US with his mother, Rose, estranged from Little Dog’s father, and grandmother, Lan.

They live in a cramped apartment in Hartford. Rose works long hours in a nail salon as the family struggles to get by. Rose, experiencing PTSD because of her childhood during the Vietnam War, suffers outbursts of rage toward her son, yet Little Dog remains abidingly loyal, even in the face of her anger. In these passages, Vuong as poet deepens the storytelling:

“…because I am your son, I said, ‘Sorry.’ Because I am your son, my apology had become, by then, an extension of myself. It was my Hello.”

The book’s poetic sensibility runs in contrast to the portrayal of life growing up poor in Hartford, Connecticut. Vuong’s alter ego, Little Dog, experiences American life in a way his mother and grandmother never can. “Each morning after that, we’d repeat this ritual: the milk poured with a thick white braid, I’d drink it down, gulping, making sure you could see, both of us hoping the whiteness vanishing into me would make more of a yellow boy.”

A Legacy of Mixed Heritage

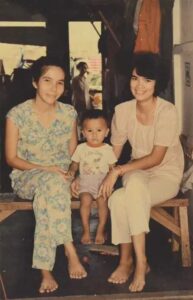

At two years old, the author, Ocean Vuong, who was born in Hồ Chí Minh City, fled Vietnam with his mother when she was targeted by authorities. The daughter of a Vietnamese woman and an American soldier, as a person of mixed heritage, under Vietnam’s laws, it was illegal for her to work.

The family—Ocean, with his mother, and grandmother—settled in Glastonbury, outside Hartford, Connecticut, where On Earth takes place, and where Vuong attended school before leaving for Brooklyn College to study 19th-century English literature and later receiving his MFA. in poetry from NYU. In 2014, Ocean received the Ruth Lilly/Sargent Rosenberg fellowship from the Poetry Foundation, and in 2016, a Whiting Award and the 2017 T. S. Eliot Prize.

He is the recipient of many other literary prizes, including a MacArthur Fellowship. He is also the author of two books of poetry, Night Sky with Exit Wounds (2016) and most recently, Time is a Mother, which Penguin Press will release this week.

Seeing Personal History Through the Prisms of War and Erasure

This is a deeply personal book, one in which Little Dog writes to his mother, Rose, who has never learned to read. The premise allows Vuong to navigate the tensions between his own American life and the one his mother lived—it’s a story of how Little Dog sees his own history in the narratives of war and erasure, but of how both are carried in the idea of his name:

“…in the village where Lan grew up, a child, often the smallest or weakest of the flock, as I was, is named after the most despicable things: demon, ghost child, pig snout, monkey-born, buffalo head, bastard—little dog being the more tender one. Because evil spirits, roaming the land for healthy, beautiful children, would hear the name of something hideous and ghastly being called in for supper and pass over the house, sparing the child.”

The Coiled Charge of its Possibility

At fourteen, a tobacco farmer outside Hartford hires Little Dog, and his work there brings a new facet of experience and agency. He meets Trevor, grandson of the crew foreperson, and the two form a close bond. Trevor will become the great love of Little Dog’s life, and with that love, sexual awakening for both. Though it subjects them to the abuse of Trevor’s alcoholic grandfather, Buford, even in a passing description of Trevor, such as this one, Vuong’s deeply reflective prose is especially poignant:

“There was something about the way he looked when lost in thought, his brow pinched under squinted eyes, giving his boyish face the harsh, hurt expression of someone watching his favorite dog being put down too soon.”

Briefly Gorgeous Observations Show Us The Worlds Within The Characters

“What I felt then, however, was not desire, but the coiled charge of its possibility, a feeling that emitted, it seemed, its own gravity, holding me in place. The way he watched me back there in the field, when we worked briefly, side by side, our arms brushing against each other as the plants racked themselves in a green blur before me, his eyes lingering, then flitting away when I caught them. I was seen—I who had seldom been seen by anyone.”

At the novel’s conclusion, the threads that link Little Dog with his grandmother’s stories, his mother’s rage, and his love of Trevor coalesce into a document of generational trauma, of what it is to be invisible, but also being seen.

Other Resources of Interest

Listen to an interview with Ocean Vuong on Fresh Air, on his most recent book of poetry, Time is a Mother.

Read my earlier review of this book and how my thoughts have changed in a LitStack Rec from 2022. And also read our post Pushcart Prize 38, briefly discussing Ocean Vuong’s powerful poem Self-Portrait with Exit Wounds.

~Lauren Alwan

As a Bookshop, Amazon affiliate, LitStack may earn a commission at no cost to you when you purchase products through our affiliate links.