Two LitStack Recs this week! How fantastic is that? Take a look at the books we think deserve another look.

In this LitStack Rec:

If you’re devoting some of your time to a work-in-progress, here are three classics of writing craft to see you through.

Reading Like a Writer: A Guide for People Who Love Books and for Those Who Want to Write Them, by Francine Prose

In this collection, comprised of a series of careful readings, Prose provides guidance for those who want to improve their skills of reading and writing. In eleven chapters, she covers the essentials in chapters that cover “Words” and “Paragraphs,” to more complex fictional elements like “Narration” and “Character.” Her simply-titled chapters unpack craft as a lens through which she examines works of fiction. Part of what makes her book so valuable is the work she chooses. Rather than iconic stories an audience is apt to already know, Prose chooses those that reflect her own taste as a reader, which is of course what the book proposes alongside scrupulous craft: a cultivation of one’s own taste.

The excellence of Prose’s choices make for ideal examples, such as Rebecca West’s novel The Birds Fall Down, as here, for sentence quality: “One afternoon, in the early summer of this century, when Laura Brown was just eighteen, she sat, embroidering a handkerchief, on the steps leading down from the terrace of her father’s house to the gardens communally owned by the residents in Radnage Square.” Or this, from West’s Black Lamb and Gray Falcon, which describes the moments leading up to the assassination of Grand Duke Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo: “When the car went by and he saw that the royal party was still alive, he was dazed with astonishment and walked away to a cafe, where he sat down and had a cup of coffee and pulled himself together.”

Both examples demonstrate the clarity, sense of intimacy and concision that marks a great sentence, or as Prose puts it, “a sentence in which we find an entire way of life.” Her book is filled with such moments, is memorable for its clarity and insight.

How Fiction Works, James Wood.

How Fiction Works is organized in a way similar to the Prose, though Wood’s chapters look both at craft topics as well broader examinations. These include “Dialogue,” for example, and “Flaubert and the Rise of the Flaneur”—one of my favorites. That particular chapter focuses on point of view, or more specifically, a character’s thoughts (walking down the street, for example) and the effects of of this expository digression that exposes character, setting, and detail. As Wood observes, the internal view demands an imposition of a style, an approach to how one aims to treat the language that describes a character’s unfiltered thoughts. Will it reflect the writer’s sensibility or interest in language, or simply convey the facts? Here is Wood on the effect of Flaubert’s discursive style:

…he is at once a realist and a stylist, a reporter and a poet manqué. The realist wants to record a great deal, to do a Balzacian number on Paris. But the stylist is not content with Balzacian jumble and verve: he wants to discipline this welter of detail, to turn it into immaculate sentences and images…

That blend of examination—which often feels so precise as to be surgical (in the best way)—along with Wood’s critical eye, make this book, for this reader anyway, a master class in close reading.

You’ve Got to Read This: Contemporary American Writers Introduce Stories That Held Them in Awe, ed. Ron Hansen and Jim Shepard

This anthology has been on my shelf since it first appeared. If you have yet to encounter this widely appreciated and influential book, you are in for a treat. Though not strictly on craft, this classic anthology of short stories offers the responses of accomplished writers who introduce some of their favorite, and iconic, works: Tobias Wolff on Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral,” Amy Hempel on Tillie Olsen’s “I Stand Here Ironing,” Russell Banks on Eudora Welty’s “No Place For You, My Love.” This was where I first read “Guy de Maupassant,” Isaac Babel’s iconic story, introduced by Francine Prose, and the hypnotic “A Distant Episode,” by Paul Bowles, introduced by John L’Heureux.

As L’Heureux writes, Bowles’ story is “something very rare in contemporary literature, a story that partakes of the visceral power and primal intelligence of legend and myth.” The introduction unpacks character, in this case a professor of linguistics who enters the “dark seductions” of a place he thinks he knows, but doesn’t.

“The land of intellect,” L’Heureux writes, “in the person of the professor is about to encounter its primal past and, like it or not, he stand in for us, he takes us with him.”

How does Bowles achieve this? Through action that unflichingly delivers his Professor to the story’s dark heart, and a “cool, disengaged voice of a narrator whose diction is elegant, whose tone is indifferent.” That observation alone cracked the story open for me, and revealed the startling contrast between the story and how it is told. You’ve Got to Read This is filled with similarly instructive points.

~ Lauren Alwan

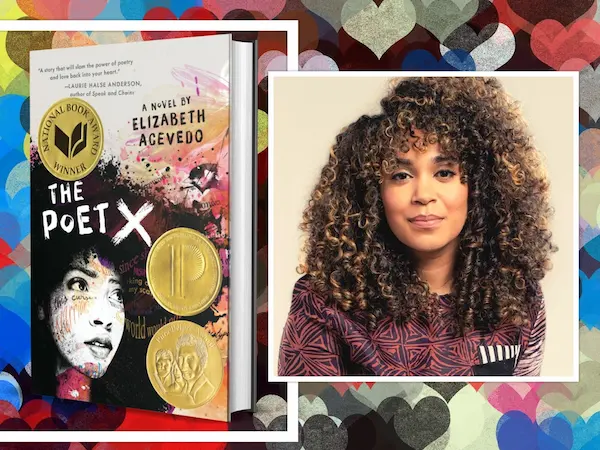

The Poet X, by Elizabeth Acevedo

While awards are only one indicator of the potential of any given literary work, when a novel wins the Michael L Printz Award and the Pura Belpré Award from the American Library Association, as well as the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, it’s a pretty good bet that it is going to be a good read.

What I wasn’t ready for was just how good this one is.

Xiomara Batista is a 15 year old first generation Dominican American girl who lives in modern day Harlem. Bombarded by the traditional expectations of her devoutly religious mother and the attention her maturing body attracts from the males in her neighborhood, she feels both ignored and unable to hide, angry, retreating instead into the poems that she sequesters away in her journal.

When a supportive teacher coaxes Xio to a spoken word club, and then local poetry slams, she discovers that her poems are more than simply words on a page – they are her voice, and they are powerful. But this newfound sense of self, along with an unexpected attraction to a boy in one of her classes, sets up a family conflict that threatens to rip her world apart.

Written entirely in verse, this book – Elizabeth Acevedo’s debut novel – is extremely effective. The lyrical voice of Xio takes us intimately into not only her thoughts, but her feelings, and they are achingly beautiful:

I am the baby fat that settled into D-cups and swinging hips

so that the boys who called me a whale in middle school

now ask me to send them pictures of myself in a thong.The other girls call me conceited. Ho. Thot. Fast.

When your body takes up more room than your voice

you are always the target of well-aimed rumors,

which is why I let my knuckles talk for me.

Which is why I learned to shrug when my name was replaced by insults.

I’ve forced my skin to be just as thick as I am.

The poems are short, pointed, cutting right to the heart of Xio’s pain, her joy, her confusion, her fear. The other characters in her world – not only her religious mother and remote father, but her brainy twin brother, her best friend since childhood, the boy who delights and disappoints her, the kindred spirits in the poetry club – all come into sharp yet tensile focus.

While much of Young Adult lit strives for some kind of originality in its confusion and conflict surrounding sexuality, relationships, and the transition between childhood and becoming an adult, The Poet X is able to address these issues with a freshness and both artful and contemporary. True to its source, genuine in its voice, compelling and heartbreaking, The Poet X is more than just the sum of its awards – it’s a masterful work of art.

~ Sharon Browning

Other Books by Elizabeth Acevedo

Other LitStack Resources

Be sure and check out other LitStack Recs, as well as articles by Sharon Browning and Lauren Alwan.

As a Bookshop, Amazon affiliate, LitStack may earn a commission at no cost to you when you purchase products through our affiliate links.