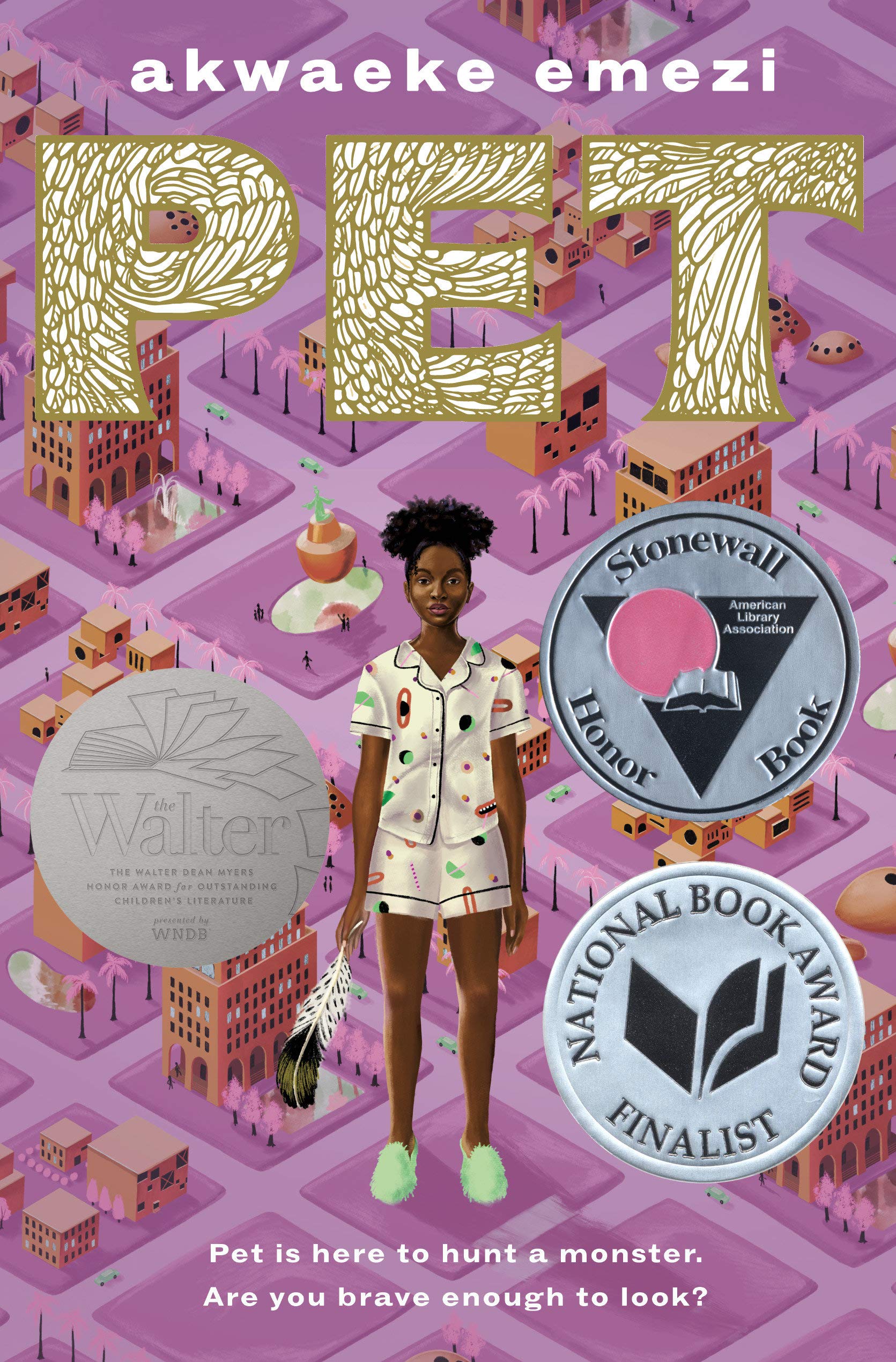

Pet, by Akwaeke Emezi

Sometimes, less is more. And in Akwaeke Emezi’s young adult novel, less is sublime.

Pet is a story about Jam, a young girl who lives in the town of Lucille. Lucille used to be overrun with monsters, until angels rose up and in a harsh battle, defeated them. The angels – now revered town elders – remain but are weary and subdued, for even in a battle against monsters dark things had to be done, things that are best not talked about now the threat is gone.

Jam is close to her father, who is a paramedic, and her mother, an artist. Life is good. But then one night Jam sneaks into her mother’s studio to see a painting that her mother has just finished, and unintentionally summons from it a creature from another plane of existence – a hunter of monsters. And this fearsome creature says that the monster it is hunting is right there in Lucille. Now Jam has some decisions to make – and none of them are easy, and none of them feel right.

The storyline is compelling enough, but it’s how this storyline is told that sets this book apart from so many others. Pet deals with many, many complicated issues – not the least of which is how to determine is something is a monster or an angel – but it does so in such a simple, unburdened way, that the essence of the story – and the characters – come shining through.

For example, Jam is a transgender character. Nonverbal by choice; she communicates by signing unless she feels it’s important enough to speak. She can feel her house communicating with her, she is sensitive to others’ thoughts and emotions. But none of this is considered strange or in need of more than a cursory explication (such as her parents’ loving apology when she asserts her gender identity in a temper tantrum – her first spoken words were “Girl! Girl! Girl!”). Because they are treated in such a unassuming way, they are accepted without distracting from the central theme.

The conflicts that the creature from the painting bring are huge and complex, but the creature itself, while mysterious in origin or even in categorization, is so singular of purpose that there is no ambiguity large enough to disturb that. (How can something be so menacing and yet so clear of purpose – a purpose that seems to be, for wont of a better word, honorable?)

There is no family conflict, except when Jam’s parents’ desire to protect her hinders her journey. The town of Lucille is full of loving, connected people. “We are each other’s harvest. We are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond,” – a quote from Gwendolyn Brooks – is the town’s mantra, during the revolution, and afterwards. There is friendship, there is affection, there is culture and beauty.

Which makes it even harder to believe that monsters may again be lurking in Lucille.

Even the writing is simple. Although Lucille appears to be somewhere in the Caribbean – endearments such as doux-doux and foods such as saltfish buljol appear without explication – there is no sense of “other”. Instead, there is a strengthened bond around the community, reinforced by the lilt in the language, the commingling of the families, the acceptance of the text of what is, is what is. The relationship between Jam and her friend Redemption is everything a friendship should be.

Even the names of the characters are simple: Jam, her parents, Aloe and Bitter, her best friend, Redemption, his parents Malachite, Beloved, and Whisper (yes, three parents) – sometimes the names have a deeper meaning, sometimes not.

All this makes us feel vested in the story, regardless of where we come from. And in doing so, we are able to embrace the larger issues without encumbrance of judgment; our understanding is moot, and so very welcome in so being. This is a wonderful book, for young adults, yes, but for all of us, as well.

—Sharon Browning