The Vexations: a novel, by Caitlin Horrocks

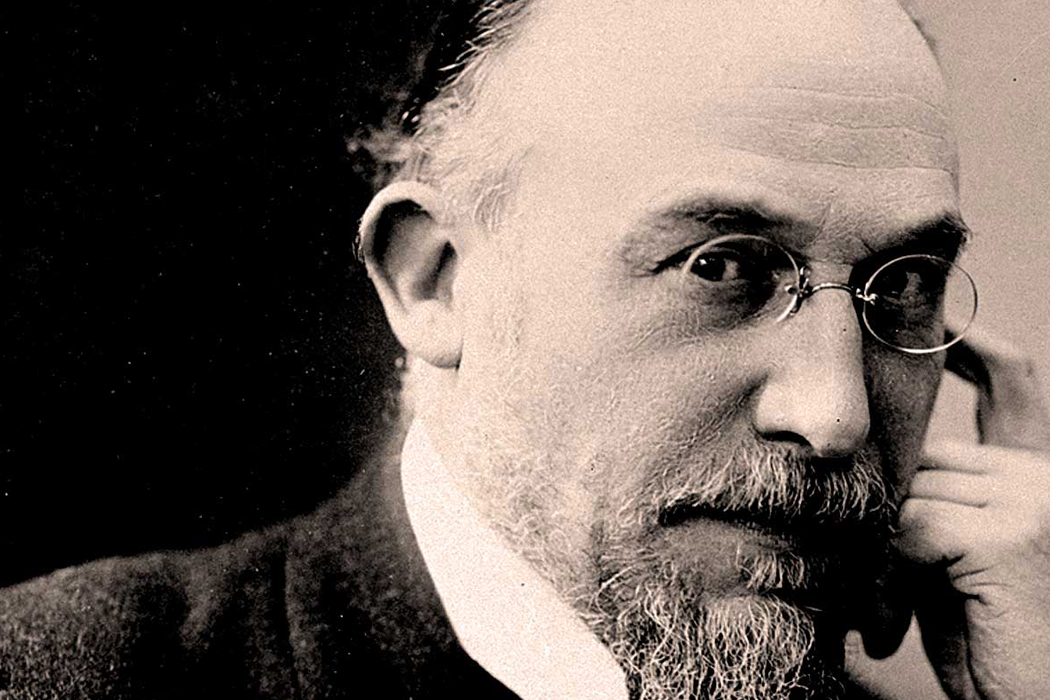

The lives of artists should portray artmaking for the work it is, anything else is a romanticized view, and Caitlin Horrock’s debut novel, The Vexations, is an intricate portrayal of the life of modernist composer Erik Satie—and his artmaking—that mines his most nuanced sensibilities: his grandiosity and impossibly high standards, and a painstaking nature that extends beyond his art to his clothing, his living space, even the color of the food he eats (that would be white). The Vexations is a novel you can escape into, accompanying the characters in their most private thoughts—the pleasures and the melancholies—to unpack the spirit behind the art.

Through shifting narrators, we glean Satie (who in his coming of age changes the c in his name to k), his younger sister Louise, their youngest brother Conrad, along with a Spanish writer, Phillipe, and Suzanne Valadon, the object of Erik’s brief affections.

Eric Alfred Leslie Satie was born in 1866 Honfleur, Normandy, the eldest of three, but at age six, his mother died post-childbirth. His grief-stricken father, Alfred, “a lightning-struck tree,” is unable to parent the children, and relocates the family from Paris back to Honfleur to live with their paternal grandparents—telling the children they are on a holiday. The grandmother, Agnes, is austere and devoutly Catholic, and unwilling to care for three children. Soon after, the

siblings are separated. Agnes sends Eric to board at the same school his father attended, while Louise is sent to live with their great-uncle Fortin and his wife, Estelle, and Conrad goes back to his father, who has by now remarried. That year, Eric begins piano lessons and from the beginning is an unconventional student, intent to “recapture the music he heard in his head.” Yet Eric “does not feel born to fame, nor entitled to it. Greatness sounds like a lot of work, frankly, and he is not given to study, or to practicing his piano.” All the same, he arrives in Paris, studies briefly at the Conservatoire where he’s labeled untalented, and begins working as an accompanist at the famed Chat Noir. By age 21, he described himself as a “gymnopedist,” establishing early on what will be distinguishing, and often destructive, eccentricities. He also identifies with the term “phonometrician” (a measurer of sounds), rather than a composer, his aim squarely on the avant-garde.

The middle child, his sister Louise, is the character with whom this reader most deeply engaged, and it’s her narrative that evokes most strongly the novel’s sense of separation, distance, and loss. For Louise, who grows up in a paternocratic French system of laws and customs, the world offers none of the advantages and autonomy it does her brothers—whether of family or finances or even maternity—and tragically, these inequities define her. Well-educated, smart, and a skilled pianist, she is re-introduced to her brothers after 15 years, Louise is shocked that her younger brother Conrad refers to Eugenie, Alfred’s second wife, as “mother.” It’s another instance of their past as one of distance—and for Louise, foreshadows losses to come.

The Vexations circulates around these early ruptures, and as the three siblings come of age, we see how each is affected. For Eric, who from the start is gifted, an instinctive composer for whom “no one could measure up,” greatness comes early. At 22, in the bohemian Paris of Montmartre, he composes what will become the most famous of his works, the spare and haunting Trois Gymnopédies (1888). Yet he’s dismissive of all but the few whose work he deems worthwhile. Friend and collaborator Phillipe observes: “Erik rarely spoke of his family. He pretended he had come into the world fully formed, as though spawned by Muses and sprung from Zeus’s head. When they went out he was charming, with a talent for wordplay that no amount of alcohol ever blunted.”

Conrad’s narrative, in contrast, shows us the view of the sibling who is not an artist—he grows up to be a chemist for a parfumerie—but who must grapple with the often inexplicable desires and motives of his brilliant and celebrated older brother, and the desperation of his talented and undervalued sister. Louise marries and bears a son, but must eventually leave everything she knows for a reinvented life in Buenos Aires. There, she gives in-home piano lessons (throughout her life the pianos she plays always belong to others), and teaches Spanish in the resettlement houses for refugees displaced in World War Two. There is a rich, elegiac quality to Louise’s story, perhaps because it’s told in hindsight, in first-person, and from the perspective of her later years. It’s a vivid portrait of a woman whose talents go unseen because of the time and place into which she’s born.

The novel’s title is refers to Satie’s most enigmatic piece, The Vexations (1893), a half-sheet of notations meant to be played 840 times in succession (a performance that would take 18 hours), accompanied by the mysterious instruction, “It would be advisable to prepare oneself beforehand, in the deepest silence, by serious immobilities.”

Caitlin Horrocks is author of the story collection This Is Not Your City, a New York Times Book Review Editor’s Choice and a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers selection. Her stories and essays have appeared in The New Yorker, The Best American Short Stories, The PEN/O. Henry Prize Stories, The Pushcart Prize, The Paris Review, The Atlantic, Tin House, One Story, and others. She is an Editor-at-Large for the Kenyon Review and teaches at Grand Valley State University, and in the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College.

Read an interview with Caitlin Horrocks here.

—Lauren Alwan