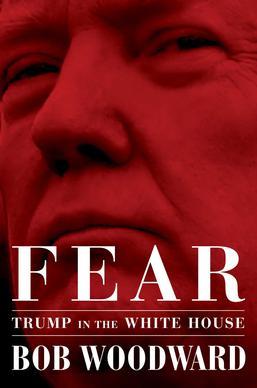

Fear: Trump in the White House, by Bob Woodward

The story has been called a bookend to Richard Nixon’s, a tale of hubris, an account akin to a ticking clock. Of Bob Woodward’s Fear: Trump in the White House, George Packer wrote in the New Yorker, the book “belongs on a shelf with the literature of mad kings, next to Robert Graves’s ‘I, Claudius,’ featuring the Roman emperor Caligula, and Ryszard Kapuściński’s ‘The Emperor,’ about the last days in the court of Ethiopia’s Haile Selassie.”

Fear covers the events leading to the 2016 presidential campaign through March 2018, when John Dowd, former DOJ attorney and “one of the most experienced attorneys in white-collar criminal defense,” resigned as

personal counsel to Donald Trump. The book’s title is taken from Donald Trump’s definition of power. “Real power” he’s said, “is fear.” Though an alternate title of the book might also be Chaos, as in Woodward’s legendary meticulous style he details the chaos of the campaign, the chaos of the transition, the chaos of meetings, and the chaos created by an absence of policy process between the president, his cabinet, and staff.

Like many good stories, this one is composed of braided narratives, each based on “deep background” Woodward conducted in interviews with current and former White House staff. It’s clear from the stance the author choose to portray principles such as Dowd, Steve Bannon, Gary Cohn, Reince Priebus, and Rob Porter, that they were candid about events—what was said, how they felt, and how they responded. As here, when after the election, Steve Bannon is shown preparing for the transition. Here, we’re in Bannon’s head, seeing his thoughts unfold:

After a few hours of sleep, Bannon started flipping through the transition documents. Garbage supreme, he thought. For secretary of defense they listed some big campaign donor from New Hampshire. Unbelievable. Now there were 4,000 jobs to fill.

There’s also Lindsey Graham, who acts as a kind of presidential narrator, appearing on the scene at crucial moments to unpack the complexities of decisions on North Korea, Afghanistan, Charlottesville, and the Syrian air strike—to name but a few—while at the same time building up the president’s ego. There’s more than a whiff of opportunism in Graham’s advisory, as when he raves, “God bless you for undoing the damage done in the past eight years. Where do you want to go? What do you want to be your legacy? Your legacy is not just undoing what he did, but it’s putting your stamp on history.”

Woodward’s portrayal of the vice-president is likewise telling, showing him to be a man who tiptoes around the president in order to stay out of his line of fire—both verbal and digital. Though when it comes to line of fire, Rex Tillerson and Reince Priebus see some of the worst. Both learned of their dismissal via Twitter, as did presidential aides who understood such decisions to be still in progress, certainly not yet public information. The president’s drive to derail decisions by undercutting established process via tactics like a premature tweet appears to be one of his favorite ploys of—one can only guess—his promise to “shake up Washington.” But in the end, those tactics only raise the ire of his White House staff.

The standout tragic figure here is Dowd. The arc of his ten months representing Donald Trump begins confidently. Working in tandem with Ty Cobb, the two aim to be transparent with the Special Counsel, and release 1.4 million documents to Robert Mueller’s investigative team. Dowd is committed to transparency, and to answering any and all questions, but in time he comes to see the impossibility of Trump testifying. There’s an astounding scene in which Dowd, with Jay Sekulow playing the part of Mueller, coaches Trump in a mock interview that ends with Trump bitterly dismissing the entire effort as “a goddamn hoax.” And though the president vacillates, in the end he’s confident he can be a compelling witness for Mueller. Dowd can’t in good conscience represent the president if he insists on an interview under oath, a situation the attorney knows will lead to perjury. In the end, Dowd utters the now-famous line, “Don’t testify. It’s either that or an orange jump suit.”

Many events portrayed in Woodward’s book echo the New York Times’ still-mysterious anonymous op-ed, “Resistance from Within,” and reveal similar strains of dysfunction—in letters pulled from desktops, rants that derail meetings, and the now proverbial assurance that there are “adults in the room.” Indeed early in Fear, Gary Cohn removes a letter to South Korean President Moon Jae-in from the Trump’s desk in the Oval Office. The letter details the president’s intent to terminate the U.S.-South Korea Free Trade Agreement, a longstanding agreement he continually fumes over as unfair, a “rip-off.” No matter how the fine points are explained, by McMaster, Mattis, Porter, or Priebus—the president fails to see how crucial national security issues are bound up with trade and maintaining troops in South Korea (a view that leads General Mattis to utter his now-famous quip about Trump’s mental acumen as that of a “fifth or sixth grader.”)

Woodward’s central premise, that the President of the United States is uninterested in facts, makes decisions based on impulse, will say pretty much anything in order to have things his way, and has to be corralled, cajoled, and flattered lest he’s made livid and explosive, is what drives events, and the point is hammered home in each of the book’s forty-two chapters. As Woodward’s shows, the forty-fifth president is not a leader, but an inciter-in-chief, reveling in the fireworks that erupt when his cabinet members and aides go at each other. Woodward writes,

The reality was that the United States in 2017 was tethered to the words and actions of an emotionally overwrought, mercurial and unpredictable leader. Members of his staff had joined to purposefully block some of what they believed were the president’s most dangerous impulses. It was a nervous breakdown of the executive power of the most powerful country in the world.

Reince Priebus put it in more colorful terms:

“…when you put a snake and a rat and a falcon and a rabbit and a shark and a seal in a zoo without walls, things start getting nasty and bloody.”

—Lauren Alwan

Lauren Alwan’s fiction and essays have appeared in The Southern Review, ZYZZYVA, Nimrod International, and other publications. Read her new column at Catapult, “Invisible History,” a chronicle of family stories of heritage and belonging and the complexities of her bicultural experience. Learn more at www.laurenalwan.com