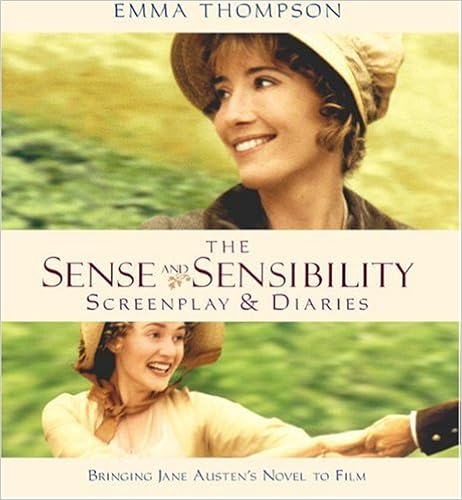

The Sense and Sensibility Screenplay and Diaries, by Emma Thompson

There’s enough left of summer to fit in at least one more light read, and Emma Thompson’s diary of the making of the award-winning Sense and Sensibility is a perfect choice. The 1995 film, directed by Ang Lee, would garner seven nominations at the 68th Academy Awards, and Thompson received the Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. This companion (published in 1995) brings together the script and the diaries Thompson kept during the six-week filming.

Thompson’s diary begins with a London production meeting. In January 1995 (the film was released the following December), there is a final discussion of the script between Thompson, Lee, and the film’s producer Lindsey Doran. That an 18th century English novel was adapted in the late 20th century by a British actress, directed by a Taiwanese-born director, and filmed in the countryside of Devon by an American production company, only adds to its layers of complexity. There’s also a backstory to the screenplay’s writing. In 1991, Doran was working with Thompson on another film, and after seeing a sample of Thompson’s dramatic writing (the actress also worked for a time as a journalist), Doran, a longtime fan of Austen’s novel, proposed the project. Four years later, as filming began, Thompson was battling depression and a disintegrating marriage to actor Kenneth Branagh, and yet she’d overcome the studio’s doubts of her abilities as a screenwriter (and later said, she was “desperate to get into a corset and act it and stop thinking about it as a script.”) She also won the role of the cerebral elder sister, Elinor Dashwood, to the passionate younger sister Marianne, played by Kate Winslet—then 19, in her first big role before Titantic. Hugh Grant (as the the modest Edward Ferrars) and Alan Rickman (as Colonel Christopher Brandon, in one of his first and perhaps best, romantic role), were cast for the love interests of the sisters—along with a supporting cast of stellar British actors, Hugh Laurie, Greg Wise, and Gemma Jones among them.

Thompson’s diary covers the fifty-eight day shooting schedule and touches on everything from a sprained wrist suffered by Winslet (nursing a bad leg, she slipped on a staircase), complications with the animal actors (a fainting sheep, and more tragically, the death of the beloved horse ridden by Greg Wise’s Willoughby), as well as numerous hangovers from late nights by the cast and crew, and bouts of bad weather. She also records the challenges, doubt, boredom, and exhaustion of working on location—the good hotels (in which firm beds and light-blocking drapes are met with gratitude), the bad weather, the impromptu parties, and the shifting moods of actors who miss family and home. Thompson records both the weighty and the trifling with equal honesty.

“Friday 28 April: 6 a.m. call. I woke at 2.30 and had a darkish time. Nice easy scene this a.m. but I feel unattractive and talentless. I look like a horse with a permed fringe. Did poetry-reading scene where Marianne teases Edward. Ate veg and rice.”

She also documents the personalities and dynamics on set.

“Lots of very cold, wet people in real rain, effects rain and mist again. Slow start. [Hugh] Laurie’s pulling his hair out….Good humor prevails I am in very fetching white wet-weather trousers and wellies. Look as if I work in a chicken factory. This was the day a very sodden Greg bounded up to Alan and asked, with all his usual ebullience, how he was. Long pause as Alan surveyed him through half-closed eyes from beneath a huge golfing umbrella. Then, “I’m dry.” Sometimes Alan reminds me of the owl in Beatrix Potter’s Squirrel Nutkin. If you took too many liberties with him I’m sure he’d have your tail off in a trice.”

Then there’s the screenplay that garnered her an Academy Award. As Devoney Looser writes in The Atlantic, Thompson makes several important departures from Austen’s 1811 novel, the most significant of which are her elaborations of the primary male characters—the love interests Edward Ferrars and Colonel Christopher Brandon. Unlike the novel, in which the characters are subdued and traditional, Looser writes, Thompson’s script revised them in a with a more nineties sensibility. “[The script] made male receptiveness to female needs and desires and a commitment to proto-gender equality seem both incredibly attractive and historically inevitable.”

This treatment of the male characters gives the film an almost contemporary feel, in which complex relationships are steeped in the genteel protocols and codes of conduct that defined gender roles in early 19th century England. The effect, for example, of altering Edward Ferrars to a man whose sees and encourages the youngest Dashwood daughter, Margaret (played by Emilie François), endows his character with greater depth, and as Looser writes, a more “evolved” portrayal of manhood:

The changes Lee and Thompson made to Austen’s original story meant the title Sense and Sensibility no longer alluded to just the characteristics of its heroines. It now applied to the heroes as well, with Rickman and Grant’s characters proving men could combine a heightened emotional sensitivity (“sensibility”) with the traditionally masculine bedrock of clear-eyed rationality (“sense”).

During the film’s production, yet another evolution took place. Thompson was introduced to Wise, the British actor whose dashing style proved perfect for the role of heartbreaker and libertine, John Willoughby. During those weeks in Devon, Wise briefly dated Winslet. Though as the story goes, after a date or two, Winslet understood there was chemistry between Wise and Thompson, and suggested he ask her out. Here’s Thompson on one of her first glimpses of him on set:

April 30: 8:20 a.m. Greg Wise (Willoughby) turned up to ride, full of beans and looking gorgeous. Ruffled all our feathers a bit.

Reader, she married him.

—Lauren Alwan