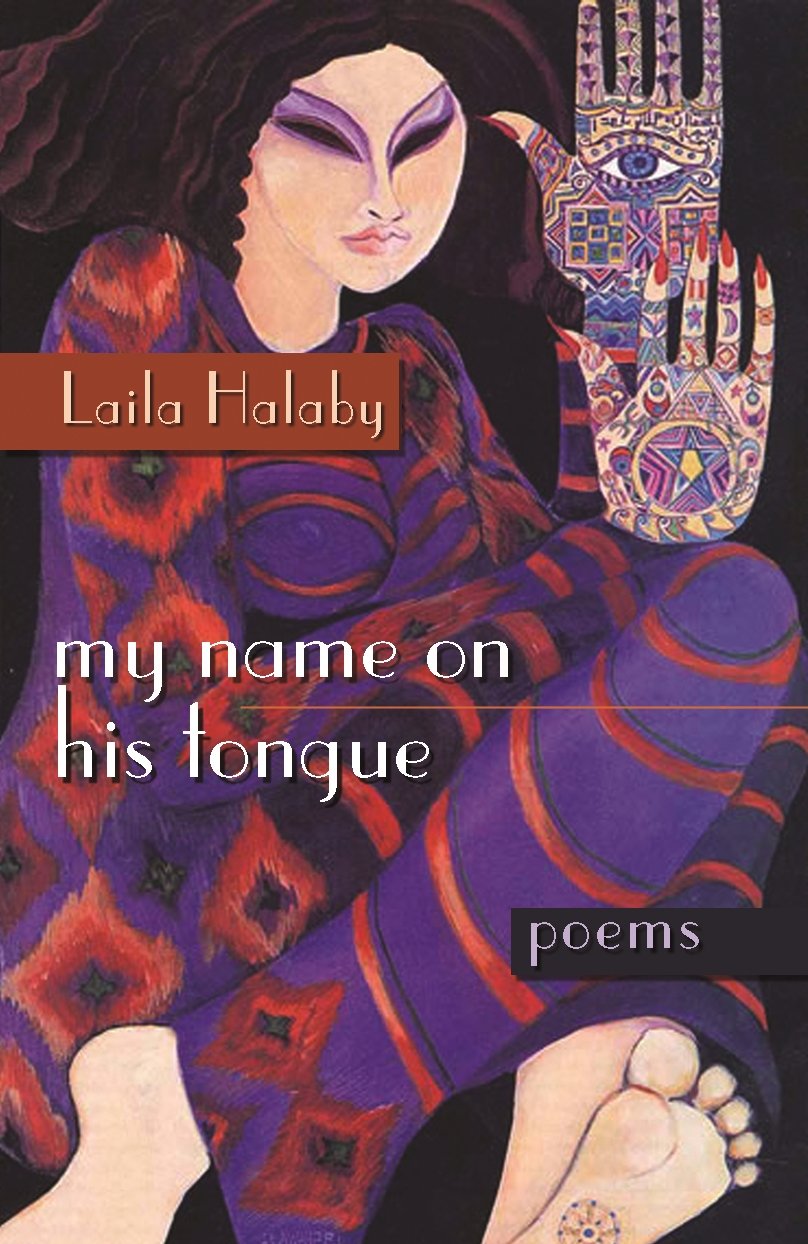

my name on his tongue, by Laila Halaby

Laila Halaby’s, my name on his tongue, her first book of poetry, published in 2012, mines issues of identity, geography, and the dislocation that comes from inhabiting two worlds. Halaby, the author of two novels and the recipient of a PEN/Beyond Margins Award, calls this volume a memoir-in-poems: a story of home, borders, arrivals, departures, airports, memory, childhood, motherhood, the Iraq war, occupied Palestine

Mahmoud Darwish, the celebrated Palestinian who spent most of his life in exile, is present in the mood of Halaby’s collection. “I come from there and I have memories,” he wrote. Though Halaby’s is a different brand of exile, having grown up between places and cultures, she mines a doubleness, or what she calls in-betweenness, described as allowing for “more immediate stories, those that demand raw descriptions.”

The collection examines Halaby’s roles as a tourist, a child, an exile, and an opponent of the wars in the Mideast and Palestine. In the poem, “how a tour guide in Petra reminded me of all I’ve lost (or never had to begin with),” a tourist in an unnamed Mideast country experiences a sudden and intense desire for a homeland. In the idea of home, the speaker charts the contradictions and ambiguity of growing up culturally and racially mixed. “I thought/I belonged /to the Whites because that/was where/my house was,” but that doesn’t prevent her from coming under, or even fearing, scrutiny: “…they questioned/my name/my face/my place of birth/my father’s absence.” Later on, she writes, “I opted for the Arabs.”

Halaby looks at the roles of exile and the outsider, a connection to person and place, and often in the context of relationships, of kinship and love. In the poem, “your country,” the uncertainty of connection becomes a metaphor: “…if I were your country/you wouldn’t be tired/in the evenings.” The poem features some of the book’s best writing, in the speaker’s voice that joins seamlessly with the subjunctive tense and stripped-down images—as here, when the speaker wonders:

if you would compose songs for me

in honor of my springtimewould you fold my cotton dresses

the way you might fold your flag

if you were allowed to show it?

In detailing the book’s origins, Halaby tells of enrolling in a poetry class the summer before graduate school. The instructor, a Kentuckian, was Joe Bolton, a gifted poet who died in 1990 by suicide at the age of twenty-eight. Bolton published three books of poetry: Breckenridge County Suite, Days of Summer Gone, and The Last Nostalgia. Of Bolton’s work, the poet Kate Benedict writes, “The persona Bolton created walks on an edge, sings from a liminal place between the present tindery moment and total combustion.”

Of Bolton and her book, Halaby recalls, “…he taught me how to read, understand and spill poems…my name on his tongue is a memoir in poems, a series of tiny stories, a collection of heartbeats and snapshots, and an homage to a teacher who unlocked the door to a rich and necessary world.” That bond gives the writer someone to write to, to write for, and for the reader, a window into the poet’s way of being and seeing the world.

Learn more about Laila Halaby here and more about National Poetry Month here.

—Lauren Alwan