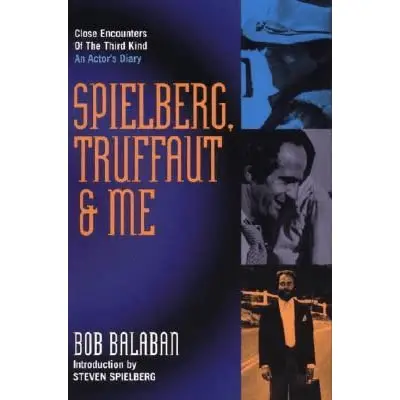

Spielberg, Truffaut, and Me: An Actor’s Diary, by Bob Balaban

In the summer of 1976, during the first weeks of filming for Steven Spielberg’s classic of extraterrestrial contact, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Francois Truffaut, who played the extraterrestrial specialist Claude Lacombe, was at work on a book about actors—tentatively titled Hurry Up and Wait. The auteur-director and founder of the French New Wave had appeared in several of his own films, as well as others, but he had trouble finding the book’s focus, and the project was never finished.

As it turned out, a book was written on that subject during that shoot, not by Truffaut, but by his co-star Bob Balaban. Spielberg, Truffaut and Me: An Actor’s Diary was published in 2002, and it’s a fascinating look behind the camera. At the time of the film’s making, Balaban had already earned film credits such as Midnight Cowboy and Catch-22. Now an acclaimed producer and director, Balaban’s hunch that Close Encounters was a singular project, and one that offered a fascinating backstory, turned out to be right.

A Diary of Filming Close Encounters

Balaban recounts the process of the film’s production, from his own casting as David Laughlin, the cartographer whose conversant French finds him suddenly recruited as Lacombe’s interpreter, to location shoots in Wyoming, Alabama, the Mojave Desert, and India. Balaban faithfully records the daily reality —the boredom, the creativity, and on-the-spot inventiveness, as well as the bonds that were forged in what became a tight-knit community far from home (for more on that sense of film family, see Truffaut’s classic film about films, Day for Night).

Balaban reveals much about an actor’s daily life on set. “Acting in a movie,” he writes, “especially one with the scope of Close Encounters, can be a difficult experience. You spend very little of your time doing what you are actually hired to do—act.”

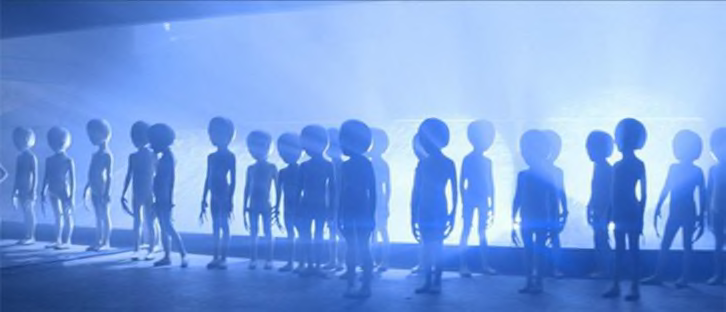

He also documents the complexities of making a film of this magnitude. Close Encounters was filmed pre-CGI, and each special effect had to be constructed in analog. This included the alien ships created by production designer Bob Alves and his team. The details include the now-iconic clouds generated by the mothership (a mix of paint roiling in fresh and saltwater), as well as the otherworldly atmospheric effects caused by the ship’s innumerable lights—a haziness created by shooting the model-sized ships through veils of smoke in a black velvet room.

A Monumental Sound Stage and Devil’s Tower, Wyoming

Spielberg’s previous film, Jaws, brought the director acclaim, blockbuster status, studio backing, and the exorbitant budget for CE3K. While that first film’s central prop was the famous (and famously malfunctioning) great white shark, Close Encounters had a sound stage of unprecedented size. The famous airstrip behind Devil’s Tower, site of the mothership’s landing and subsequent contact (of the fourth kind) with humans on earth, was constructed in an immense abandoned dirigible hanger on a disused airbase outside Mobile, Alabama. As Balaban notes on first seeing the set:

“…spread out below me is an astonishing sight: a long, concrete landing field stretches out for what looks like miles. It is surrounded by piles of rocks which look exactly like the rocks at the base of Devil’s Tower. It’s as if we never left Wyoming.”

As Spielberg proudly shows off the upper reaches of the immense set to his principal cast, Balaban writes, “The stairs are really shaking now, and I hold on to the wooden support slats with both hands. Nobody seems to mind. Truffaut is fascinated by all of this. I try to translate [Truffaut’s French] for Steven, but my translation gets vaguer as my vertigo increases.”

Balaban also looks at the more ordinary detail of what it’s like to work on location. This actor’s diary shows us Truffaut and Balaban on their first night meeting in Gillette, Wyoming, walking out of a local restaurant because a country-western band is blaring, and Truffaut can’t stand loud music during dinner. We see the extras who are fired due to excessive beer consumption, and the protest they mount at learning they have to cut their hair in order to look like government aerospace workers. There is Balaban and Truffaut, grabbing lunch in an A-frame cafe at the base of Devil’s Tower, which for the film sports a sign that reads “Decontamination Camp.” Balaban also reveals his regret at the ordinary trousers and jacket he brought for his character of Laughlin after seeing Truffaut’s superbly tailored Parisian clothes.

We learn too that Balaban was not completely confident in his ability to speak French, even with the carefully prepared lines he’d brought to the audition. Truffaut too was self-conscious, and good-humored, about his English, and this mutual challenge around language forged a bond between the two, one that continued until Truffaut’s death in 1984.

CE4K—A Classic of the Genre

Balaban’s hunch that Spielberg’s extraordinary film, with its groundbreaking visuals and singular cast, warranted daily journaling, was prescient. The film has become a classic of the genre, and notable as the only American film in which Truffaut appeared, despite the director’s lifelong devotion to and exhaustive knowledge of American cinema.

Spielberg, Truffaut and Me is a memoir filled with fascinating detail of what it’s like to make your living as an actor and live a life that centers on making films.

—Lauren Alwan

Lauren Alwan’s fiction and essays have appeared in The Southern Review, ZYZZYVA, Nimrod International, and other publications. Read her column at Catapult, “Invisible History,” a chronicle of family stories of heritage and belonging and the complexities of her bicultural experience. More at www.laurenalwan.com