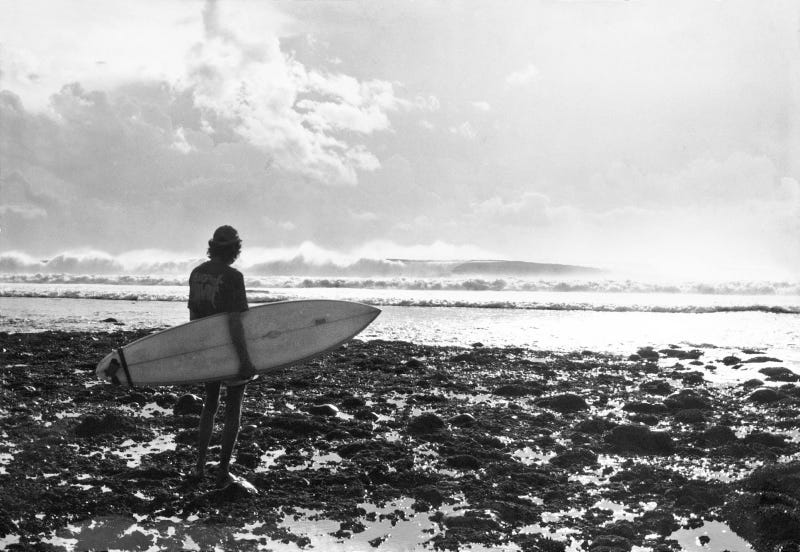

Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life, by William Finnegan

William Finnegan’s 2016 memoir begins with an epigraph from Edward St. Aubyn’s novel Mother’s Milk:

“He had become so caught up in building sentences that he had almost forgotten the barbaric days when thinking was like a splash of colour landing on a page.”

It’s a fitting introduction, in parts touching on writing, water and the obsessions that can take hold with both. An international journalist and staff writer for the New Yorker, Finnegan wrote the book over fifteen years between assignments here and abroad. A longtime reporter of international politics, prior to this memoir he’d written on the effect of poverty on American teenagers, the drug war in Mexico, and immigration reform. But as Barbarian Days, winner of last year’s Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction shows, for Finnegan, surfing was always there, and could well be considered an obsession, as well as a spiritual practice, and a calling.

He spent his early years in L.A.’s San Fernando Valley, at eleven years old, until the family moved to Hawaii. Finally able to surf every day, Finnegan learns to ride, and read, the waves. One of the pleasures of this book is Finnegan’s skill at describing surfing in a way that is understandable for the non-surfing reader. It’s a window into what it’s like to grow up surfing, learning to understand how winds and distant storms and temperature and tides drive to the speed, shape and behavior of waves. During those first forays in Honolulu, he writes: “I began to learn the tricky, fast, shallow sections, and the soft spots where quick cutback was needed to keep a riding going. Even on a waist-high, blown-out day, it was possible to milk certain waves for long, improvised, thoroughly satisfying rides. The reef had a thousand quirks, which changed quickly with the tide. And when the inshore channel began to turn a milky turquoise—a color not unlike some of the Hawaiian fantasy waves in the mags—it meant, I came to know, that the sun had risen to the points where I should head in for breakfast.”

The author was initially reluctant to write about what he calls his hobby, fearing that coming out as “a dumb surfer” would hurt his credibility as a reporter. With that, he felt a lack of urgency, he’s said, given his reporting on geopolitical events and humanitarian causes. But a defining moment for the book took place about a decade ago, when a friend unexpectedly sent a cache of letters written by the author at 13, detailing his life and early surfing experiences in Honolulu. Said Finnegan:

“It was this Proustian madeleine moment…I could see the world and I knew that this was the beginning of the book, right here. Those letters form the backbone of the first chapter.”

In this memoir, the ocean is as a touchstone: it’s there as the author comes of age, during college, as a young man traveling the world to seek out the undiscovered locales where the best waves break, and it’s there as he ages, still surfing his beloved spots at age sixty. Finnegan relates this life journey with details that allow outsiders to grasp what he’s called a study of a subculture, and does so with careful description. For example, on the art of riding a wave—in no small part a humbling act of confronting a force of nature—he writes with a clarity for those who’ve never set foot in the ocean. Barbarian Days is a primer, on the physical sport of surfing, structuring one’s life around it, but the experience of what it means when a person paddles into the surf.

In fact, waves are a kind of character in this book. From his first serious encounters at the hotspots around Oahu, to the island of Tavarua off Fiji, to San Francisco’s Ocean Beach, Finnegan shows us waves that are beautiful, threatening, complex forces of nature. “When waves are great,” Finnegan has said, “I’ll find myself dawdling on the shoulder, looking into them.” Yet many are surfed at a certain peril, even as it brings a discovery of the self, of the ocean, and the challenges of the sport itself. There is much to learn about what a wave in fact is, and does—its shape and the way it breaks, and how one who surfs it must often assess those qualities with split-second timing. Surfing is a culture that is traditionally hostile to outsiders, with knowledge that is specialized, even arcane, “like living inside a dialect that’s kind of incomprehensible to outsiders, and you either you know it or you don’t.” But Finnegan more than succeeds in allowing outsiders entry into this specialized world:

“All surfers are oceanographers, and in the area of breaking waves all are engaged in advanced research. Surfers don’t need to be told that when a wave breaks actual water particles, rather than simply the waveform, begin to move forward. They are busy figuring out more arcane relationships, like the one between tide and consistency, or swell direction and nearshore bathymetry. The science of surfers is not pure, obviously, but heavily applied.”

The analytic strain in Barbarian Days is one of its pleasures. It means the outsider can see the ocean and its waves as a seasoned surfer does. And Finnegan doesn’t hold back. Scores of reviews have reveled in the lexicon to be found here, descriptive terms—growling, durable, feathering—that reveal a singular point of view.

Barbarian Days looks at the ocean, waves, and surfing with an unprecedented depth, and looks too at friendships, both temporary and those that endure over a lifetime. There is a thread too, of otherness, of the ways in which Finnegan himself felt a fundamental distance from LA inland life, and the cultures he explored, and at times from the sport itself. For the author, there is a self-consciousness of being a haole, a white person, in Honolulu, being a foreigner working and surfing in Australia, and an honored guest of a struggling Fijian family.

Maybe the most affecting thread of the memoir, beyond the sublime passages on waves and surfing, is that of the author’s yearning for something he can’t name. From the start, as a youth learning to read the ocean in Waikiki, Finnegan writes, “…my utter absorption in surfing had no rational content. It simply compelled me; there was a deep mine of beauty and wonder in it. Beyond that, I could not have explained why I did it.” By the memoir’s end, Finnegan unpacks that mystery, and it knits the threads of his account in a beautiful and unexpected way.

Read an interview with William Finnegan on craft and career here, at CutBank, the journal of the University of Montana MFA Program.

—Lauren Alwan