Out of Place: A Memoir, by Edward Said

Edward Said, the prolific author, political activist, pianist, and music critic, rose to academic stardom in 1978 with the publication of Orientalism, a seminal critique of the appropriations and misrepresentations that founded the Western study of the East. Said, who died in 2003 after battling a rare form of leukemia, leaves an immense legacy of scholarly writings, essays, and criticism, as well as a memoir, Out of Place, and it’s one of the books I treasure.

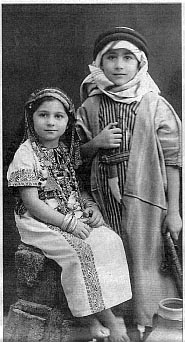

Said described Out of Place as “a record of an essentially lost or forgotten world.” In elegant and often melancholy prose, he recounts his childhood in Jerusalem, Palestine, Lebanon and Cairo, all through the lens of a “fractured status as Palestinian-Arab-Christian-American.” In the pan-Arab community of 1940s Cairo, the Saids, though financially well off, were outsiders. Classified as Shami, non-Egyptian Arabic speakers, they were also of blended Christian backgrounds, Protestant and Baptist, a trait that made them further unclassifiable. For the young Edward, a sense of conflicted identity was already forming, an awareness of having “an unexceptionally Arab family name like Said connected to an improbably British first name.” He writes of his intellectually curious ten year-old self:

“I always looked around doors that were ajar; I read books to find out what propriety kept hidden from me; I peered into drawers, cupboards, bookshelves, envelopes, scraps of paper, to glean from them what I could about characters whose sinful wantonness corresponded to my desires.”

That curiosity often brought punishment and criticism, and was treated as a flaw in his character—in fact, the memoir’s initial title was “Not Quite Right.” This early sense of difference became in adulthood an intellectual impulse to go against the grain, a desire for the difficult over the harmonious, described in terms that reflect his deep affinity for music—dissonance, counterpoint, contrapuntal—terms that also convey the fundamental disparity of an internal state in conflict with external conditions.

The deeply personal view in Out of Place gives the memoir its power and elegance of design. The displacement that occurs internally, in the formation of Said’s young identity as Edward, a construct of obedience, diligence, filial duty and moral example, is writ large in external events: the family’s departure from Jerusalem after the UN Partition in 1947, their flight from Cairo upon invasion of the Germans in 1942, the abandonment of the family home in the mountains outside Beirut at the onset of the Syrian-Lebanese Civil War of 1958. A subsequent displacement took place again when Said, at fifteen, left Cairo to be educated in the U.S., attending boarding school in western Massachusetts, and later Princeton, then Harvard.

In the course of the memoir, the dissonances, both outer and inner, evolve into what Said called a “cluster of flowing currents” perceived in the mature self. These, he said, form “all kinds of strange combinations moving about, not necessarily forward, sometimes against each other, contrapuntally yet without one central theme. A form of freedom, I’d like to think.”

As Said’s memoir so beautifully makes clear, these currents need not be reconciled or harmonized, only understood in order to see and ultimately accept the mystery of what it is to live between worlds.

Edward Said reads an excerpt from the book here.

-Lauren Alwan