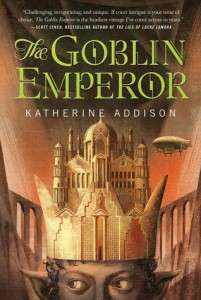

The Goblin Emperor

Katherine Addison

A Tor Book

Release Date: April 1, 2014

ISBN 978-0-7653-2699-7

I’ve never been a big fan of goblins. Or trolls. Or ogres, orcs, imps, demons or any kind of horde-ish miscreants of the supernatural world. Not even drow.

But so many people had put Katherine Addison’s debut novel, The Goblin Emperor, on their “must read” list, so many reviewers were singing its praises, that I felt I should certainly put that prejudice aside. Finally, after months of my request waiting in queue at the library, I had the chance to read it – and it certainly was not what I expected.

Ms. Addison’s novel takes place in the land of Ethuveraz, which is inhabited by elves, and is bordered on the north by Barizhan, the land of the goblins. Elves are pale, with the most elite having pure white hair and glacially blue eyes; they seem to revel in formality and obsess on matters of propriety. Goblins, on the other hand, are stouter than their elven neighbors, and less deliberate, with skin that varies in shade between smoky and coal black; their eyes can be yellow or orange or even red, and the purest of them will glow with an intensity that speaks of their fiery nature. While the Ethuverazians tend to be hostile to all outside of the their realm, and look down on their goblin neighbors as foreigners and barbarians, there is no overt enmity between the two races. It is not uncommon to see goblin merchants and servants in the Untheileneise Court (which houses the palace of the emperor and various other governmental and religious establishments); even intermarriage between the two races is not unheard of, even though tacitly frowned on in more conservative elvish enclaves.

One such marriage occurred between the current emperor, Varenechibel IV, and his fourth wife, Chenelo Drazharan, daughter of the Great Avar of Barizhan. The match between the 16 year old goblin girl and the much older elven ruler was arranged purely to bolster trade between the two countries, and as soon as the established marital rites and duties had been performed, Chenelo was ignored. That single mandatory coupling resulted in a royal pregnancy, but by then Varenechibel IV was so disenchanted with the idea of having a “hobgoblin” as a wife that as soon as she could travel after giving birth, he sent her and their infant son to the remote holding at Isvaroë where they stayed in meager surroundings until her death eight years later.

That child, Maia, was easy to ignore. With three older (and more acceptable pureblood)brothers, there was no fear that this child who took after his goblin mother would ever be required at court. That is, until tragedy struck. When Maia was seventeen (and living in ever meaner surroundings at the tiny keep at Edonomee where since his mother’s death he had been under the care of his resentful and often hostile “cousin”) Varenechibel IV and his three elder sons were killed while traveling to a political ally’s wedding, suddenly leaving the shy and totally unprepared half-goblin Maia as the next Ethuverizian emperor.

The Goblin Emperor is Maia’s story, chronicling his initial stumbles, his embarrassments, his resolve and his trials by fire; the friendships, the rivalries, the manipulations and the betrayals; the search for purpose and understanding, the struggle to do the right thing without even knowing what the right thing is, in a completely unfamiliar, hostile and incredibly complicated and convoluted environment.

Author Addison has created an amazing world in her novel, with a richness and complexity that is, at times, simply mind boggling. Trying to keep track of characters and their familial and political relationships is a daunting task, especially given that it seems like each character has as many as four different iterations of their name, given the formality of the situation and their affiliation with their correspondent, even their gender and marital status and whether they are being addressed as an individual or representing a specific ancestral House. Names – of characters, places, rituals, items, job titles – are multi-syllabic and full of vowels and/or strange (to us) consonant pairings, making them difficult to assimilate. Speech, especially elven speech, is staunchly formal, full of “thee’s” and “thou’s”, and everyone – everyone! – in polite society refers to themselves in the plural, not just royalty.

Then there are the Corazhas, who are the emperor’s advisors (along with his Lord Chancellor)designated as “Witnesses”, as in “Witness for the Justiciate” and “Witness for the Foreigners”, and so on. There are seven established parliamentary Witnesses, but then there are also Witnesses that are outside of the Corazhas, such as the Witness for the Emperor (who seems to have something to do with legal proceedings), and Imperial Witnesses (who seem to have investigatory duties), a Witness for the Dead, even a Witness for those who have no voice. Then there are Prelates and an Archprelate, an Adremaza – who are part of the maza, or priestly caste – and of course the edocharei, who are a cadre of the Emperor’s personal attendants, and the nohecharei, who are the Emperor’s personal bodyguards.

Is your head spinning yet? Mine was. The sheer immensity of this world was overwhelming. In fact, at times I really did find it frustratingly daunting… until I realized that I was being given a sense of what Maia was going through when he was plucked from obscurity to not only suddenly have to move amongst all these factors, but rule over them under intense scrutiny – doubly so due to his half-goblin parentage. Of course, the language and names and histories would have been known to him but the sense of unstable footing was shared between character and reader – a masterful stroke.

We are also given the sense that although Maia (or Edrehasivar VII Drazhar – his royal name as Emperor) is now the most powerful person in Ethuveraz, he is as much a prisoner to its confines and dictates in its richness and pomp as he was to remote poverty when he was a cast off boy in Edonomee. He is in danger – not from armies or invasions – but from within, overtly by those who feel he is not worthy of sitting on the throne, but also covertly by those more astute in the subtleties of court and protocol who strive to control him behind the guise of friendship and duty.

The Goblin Empire is indeed well written, intricate, and involving – an epic adventure, even without flashing swordplay, vaulted quests or bare-chested heroics. Watching Maia strive for footing that feels secure in the traditions of both elves and goblins, but also to himself and the legacy of compassion that his mother instilled in him, is captivating. If you are willing to invest a bit of attention – and patience – at becoming familiar with this world, you’ll be greatly rewarded. I don’t know if I would give it all the accolades that it’s received, but it’s a worthwhile read.