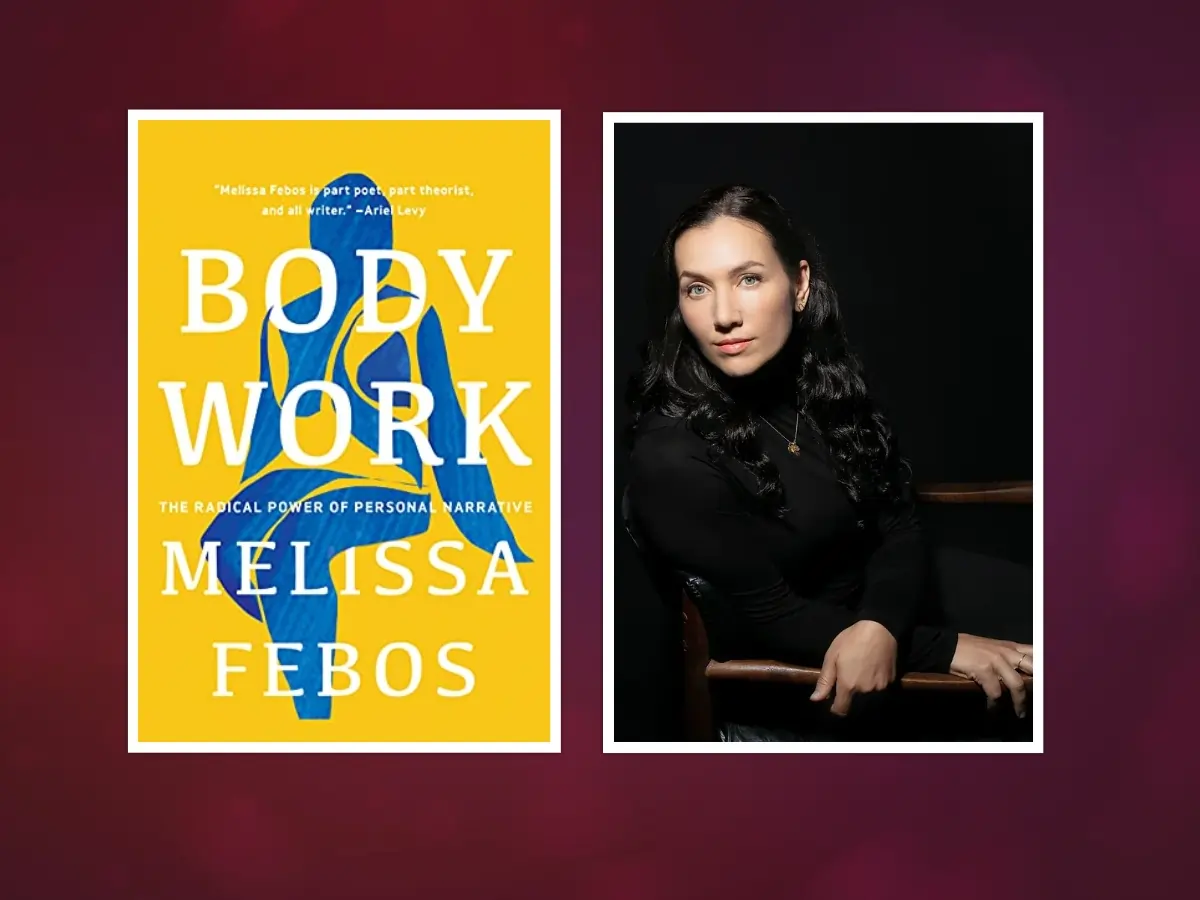

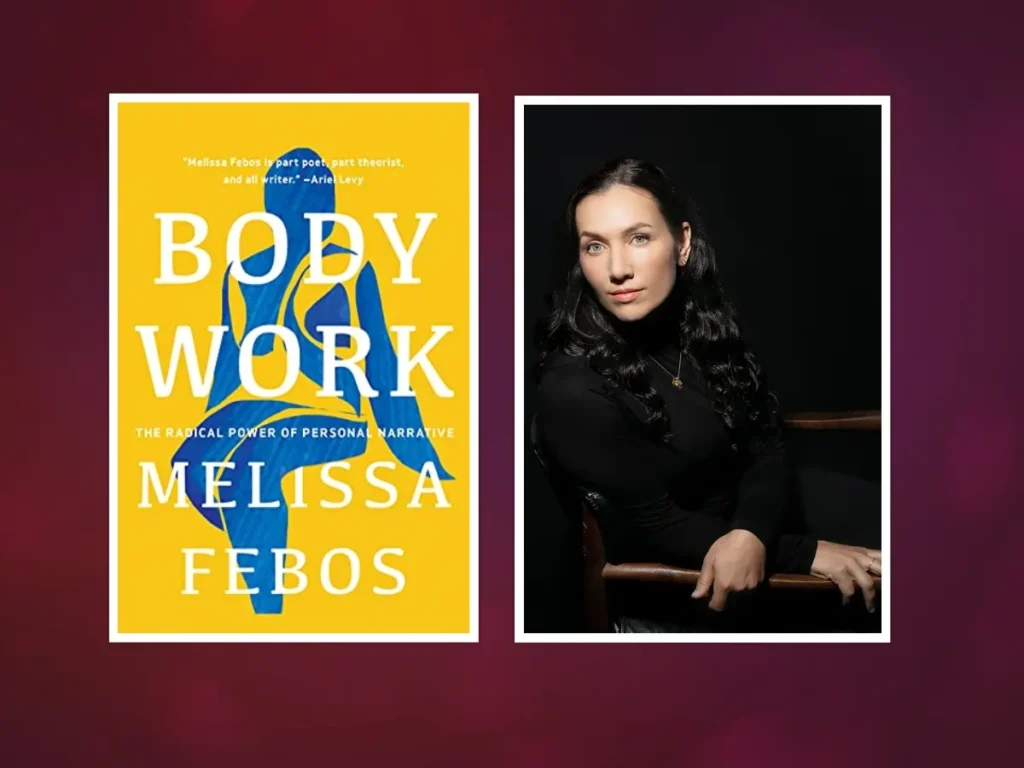

For this LitStack Rec of “Body Work,” we unpack the hidden parts of memoir. Lauren Alwan recommends you buy and read Melissa Febos‘ book Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative.

“Navel-gazing is not for the faint of heart.”

In This LitStack Rec:

A Writing Guide and Coming of Age Story

“Navel-gazing is not for the faint of heart,” writes Melissa Febos early in her gripping memoir. “The risk of honest self-appraisal requires bravery.” To write about oneself, as Febos does in this insightful and often brutally honest memoir, is to fully interrogate the how and why of the self, a process far from the indulgent act of navel-gazing. “To place our flawed selves in the context of this magnificent, broken world is the opposite of narcissism, which is building a self-image that pleases you.”

Body Work, Febos’ fourth book and third memoir, is both a guide to writing and a coming of age story—but a writer’s coming of age as she comes to know how the act of writing illuminates the self, and that each writer’s path is hers alone to forge: “I have found that a fulfilling writing life is one in which the creative process merges with the other necessary processes of good living, which only the individual can define.”

From a youth growing up questioning her life choices, to the pain of drug addiction and years as a sex worker—which the author looks at in her first book, a memoir, Whip Smart—in Body Work, Febos draws a connection between writing that mines personal history and incorporates, both in literary and emotional terms, the role of the body—the physicality that informs a writer’s sensibility, and, she argues, must be integrated into the writing process if the work is to be both artful and authentic.

By reading books she loved, The Basketball Diaries, The Bell Jar, A Spy in the House of Love, Febos recounts how she comes to understand how she can be both the architect of the story and a character in it.

Advice for Writing and Life

There is great writing advice here throughout. When writing her first memoir, she recalls, she gave a draft to every person she’d included, and the input she received was highly instructive. From those beta readers, she eventually took out much of what she felt wasn’t hers to share, or facts that “would upset that living person more than it mattered to my book.” She also observed that when a detail “felt cruel, the prose was almost always better off without it. Cruelty rarely makes for good writing.”

She also looks at the power of memory: “I suspect everything we remember has symbolic meaning, is redelivered to us as a suggestion, a lesson, a reminder, or else perhaps, a haunting, a ghost consigned to the human realm until it completes some bit of unfinished business.”

Overcoming the Disempowerment of Trauma

There is also guidance here on writing from trauma: “…all forms of trauma, from intergenerational, to historical trauma, to those of illness, mental and physical abuse, and the many wrought by war, share the qualities of disempowerment. No productive therapeutic work can be done until the traumatized patient understands that she has recouped some sense of her own agency…”

On this subject, Febos covers fascinating historical ground as well. She looks at Sigmund Freud’s well-known research on female “hysteria,” part of his work that is perhaps most widely known by the general public, and covers ground that is perhaps not as well known. Initially, Freud concluded he’d correctly diagnosed his young patients, concluding their “hysterical” symptoms were the result of “premature sexual experience,” that is, the predatory variety. And yet, he was forced to revise his theories after the wealthy families who sent his daughters to be treated by him refused to let him publish his research—knowing their entire social class would be incriminated by his findings.

Insight, not Experience, Informs the Memoir

“It is not experience that qualifies a person to write a memoir,” Febos tells us, “but insight into experience.” Successful narration of a memoir, she continues, “depends upon the careful interplay of the past ‘I’ and the present, whether it be explicit or implicit in the text.” That’s one of the most important takeaways of this book: “Self-knowledge, the insights unavailable in the past and acquired in the time since, are what give memoir its depth.”

In the end, to write about oneself, Febos advises, to chart the dark, vulnerable, or broken places, is far from the navel-gazing trope—it requires a willingness to unpack what’s been hidden, and look at it in the hard, clear light of understanding.

About Melissa Febos

Melissa Febos is the author of four books, and the recipient of a 2022 Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, a 2022 National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship, and the Jeanne Córdova Nonfiction Award from LAMBDA Literary. Her work has appeared in publications including The Paris Review, The Sun, The Kenyon Review, Tin House, Granta, The Believer, McSweeney’s, The New York Times Magazine, The Guardian, Elle, and Vogue.

The nationally bestselling essay collection, Girlhood, which was a LAMBDA Literary Award finalist, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award in Criticism, and named a notable book of 2021 by NPR, Time, The Washington Post, and others. Body Work, published in 2022, also a national bestseller, is an LA Times Bestseller, and an Indie Next Pick. Her fifth book, The Dry Season, is forthcoming from Alfred. A. Knopf.

—Lauren Alwan

Buy Books by Melisssa Febos

Other LitStack Resources

Find other book recommendations by checking out our extensive list of LitStack Recs. You can also find books to read by checking out these other articles by Lauren Alwan.

As a Bookshop, Amazon affiliate, LitStack may earn a commission at no cost to you when you purchase products through our affiliate links.