Yvain: The Knight of the Lion

Yvain: The Knight of the Lion

M. T. Anderson

Illustrations by Andrea Offermann

Candlewick Press

Release Date: March 14, 2017

ISBN 978-0-7636-5939-4

Don’t be swayed by the publisher’s information: Yes, M. T. Anderson’s graphic novelization of Chrétien de Troyes’s 12th century Arthurian legend is aimed at ages 12 and up, grades 7 and up. Yes, it is written with a younger reader’s sensibilities in mind and absolutely is appropriate for younger audiences. But that doesn’t mean it’s just for kids.

Yes, the text deals with the classic themes of honor, love and glory. There are knights and their lady loves, dragons, giants and demons in need of slaying. There are wrongs to be righted, harm to be avenged, downtrodden to be championed, justice to be meted out. But there is also fecklessness, oaths broken, callousness and betrayal.

Author M. T. Anderson (Feed, The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Symphony for the City of the Dead: Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad) treats these classic themes with respect, but also makes them accessible to modern audiences by throwing in casual, sometimes cheeky treatments that liven up the story without breaking the tone and intent of the original. (One of my favorites is the only nod to the romance between Sir Lancelot and Lady Guinevere, when King Arthur – who seems less a noble king than “a little dense and occasionally even incompetent”* – explains Lancelot’s absence by saying “He’s off fetching Queen Guinevere from some dastardly castle,” adding, “They’re great friends, those two.”)

Mr. Anderson’s take on Chrétien de Troyes’s epic tale does not shy away from the feckless reality that is dressed up in the highly romanticized notions of knights in shining armor and courtly love. While Yvain is indeed a renown knight whose reputation is bolstered by tales of honor and derring-do, he falls in love with the beautiful Lady Laudine, wife of a man he has just murdered, as he watches her grieving at her husband’s funeral. After she resignedly agrees to marry him in order to save her estate and people, he turns around and leaves her to head out with Sir Gawain in order to “prove his valor through jousting and feats of arms.” All Laudine asks of Yvain is that he be gone for no more than one year, else her love “will absolutely turn to hatred.”

So what happens? A year passes, and Yvain is having so much fun with his buddies that he doesn’t even think of leaving until a servant arrives to tell him in no uncertain terms not to return home. He then proceeds to fall into a funk and yearns for death. After wandering in the wilderness, saving a lion who becomes his companion, and supposedly overturning “Yvain the fool” to become “Yvain the man” by accomplishing honorable deeds, he heads home, convinced he can regain his wife’s love. How does he do that? By putting her lands and people in mortal danger, then allowing her to be tricked into forgiving him in exchange for protection for her castle.

That’s an awfully cynical depiction of love – nothing “courtly” about it, yet indicative of the stories that gave rise to the myth despite the manipulation and indifference regarding the desires of the woman at its core.

Yet the strongest component of M. T. Anderson’s narrative (which is taken, for the most part, directly from Chrétien de Troyes’s text) is how Lady Laudine, and her attendant Lunette (who is the pivot upon which her lady’s manipulation turns), are not marginalized characters. Both women are intelligent, knowing how to work within the constraints of their time and place to forge an unswerving sense of their own identity. Lunette is the cleverest player in this tale, able to catch the ear of both Yvain and Laudine, achieving her desired outcome by plying their emotions to her own ends. And Lady Laudine, fully understanding her role in her world, nevertheless refuses to acquiesce to Yvain’s protestations of love, remaining alternately fiery and steely cool, unwilling to relinquish her anger even as she accepts the dictates of the male-centric world around her. These truly are women to admire, despite the objectification of their sex in myth, legend and history.

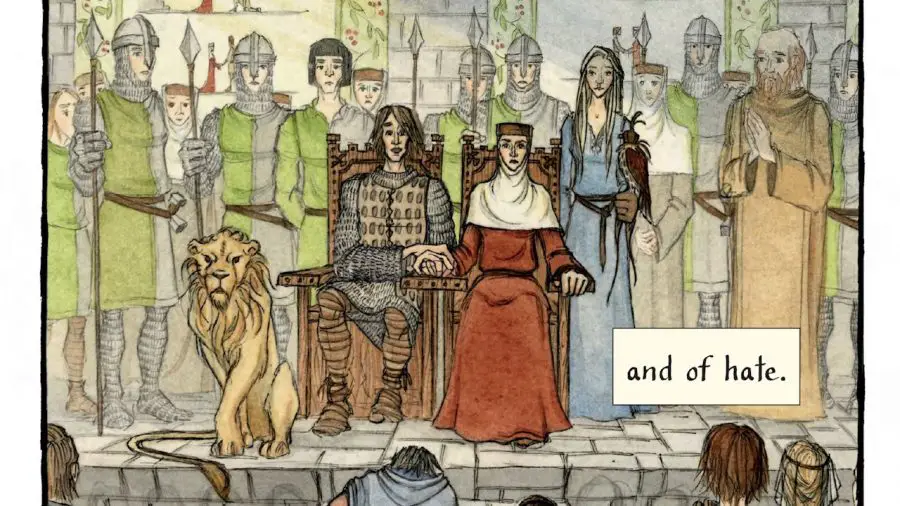

And it must be noted that Yvain: The Knight of the Lion is a beautiful book. Andrea Offermann’s illustrations are gorgeously understated and graceful, even during the liberal combat scenes. Her use of thematic colors, authentic clothes and armor, referenced locations, and the gracefulness of her characters, lend an immediacy to the story that draws in the reader so deftly, so lyrically. Not lush, but rich; not ornate but with a strength and clarity that is pleasing to the eye and soul.

A pleasure for the eye, the ear, and the mind, and oh, so much more than a kid’s book. Go ahead – treat yourself.

~ Sharon Browning

* From M. T. Anderson in his Author’s Note, speaking to the subtle irony in Chrétien de Troyes’s original text.